This morning I've been listening to A.S. Byatt being interviewed by the Australian Radio National 'All in the Mind' for National Science Week. It was a great pleasure to hear a favorite author talk about her love of science, her horror at the idea that the English Department would be the centre of the University, snail neurons, mirror neurons, her mind maps (though she doesn't use that term) and the colours of her novels (in an almost synesthesian* sense).

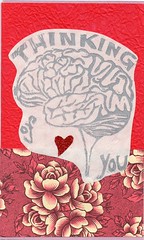

This morning I've been listening to A.S. Byatt being interviewed by the Australian Radio National 'All in the Mind' for National Science Week. It was a great pleasure to hear a favorite author talk about her love of science, her horror at the idea that the English Department would be the centre of the University, snail neurons, mirror neurons, her mind maps (though she doesn't use that term) and the colours of her novels (in an almost synesthesian* sense).I am fascinated by the intersection of art and science, and this is one of the reasons I am so fond of her novels. She quite clearly articulates that she understands what some of her more disdainful peers in literature did not; that science is very much a creative field of endeavour. Further, she explains how she develops some of the key concepts underlying her novels (specifically Babel Tower) through the process of analogy, which she links to metaphor. Byatt is quite obsessed with metaphor, as well as being very interested in neurology. As such, I always think she should read one of my other favorite authors, Douglas Hofstadter. I am always telling people they should read Gödel, Escher, Bach, and then refusing to lend it to them, because I need to have it on my bookshelf at all time.**

Hofstadter works in artificial intelligence, so he thinks very deeply about how it is we think. He feels that analogy is the core of cognition, as he explains in the amusing and unpretentious lecture included below (

I think it is quite wonderful that Byatt can look to science as a means of enriching her literature - not simply with pretty metaphors, but in a deep structural sense, and Hofstadter can look at the tiniest linguistic errors we make***, and see them as data on how it is we actually think. In the interview Byatt speaks about mirror neurons - neurons which light up both when we perform an act and when we see an act performed. This is explained as a possible source of empathy. I wonder if this mirroring (which I've seen also postulated as an explanation for how we understand facial expression) does in fact indicate that on a fundamental level we understand actions we observe directly from analogy - not just in a higher level 'software' sense, as Hofstadter tends to discuss, but in a neuron-level 'hardware' sense as well.

*Is this a word? I think it should be. I created it by analogy.

**I made an exception for the time, years ago, I convinced my friend JM to go get it signed by Hofstadter, since I had to teach when he was speaking with the grad students in our department. JM was a good sport. I confess I was actually unsure I wanted to meet Hofstadter - because I was uncertain he would match the mental construct I had formed of him in my head. This is ironic since I formed my ideas about mental constructs of people partly by reading Hofstadter's Le Ton Beau de Marot (which of course, is in English).

***He collects linguistic slips. My favorite, of the spoken errors in English by native speakers, which I have observed is one made by my friend Jill. Jill once said, "I'm turd, even though I have a chordle-neck on." I love that 'turd' came from 'turtle' and 'cold' not only swapped places with the first syllable of 'turtle', it also morphed into 'chord', because, presumably, she couldn't drop the 'r' sound. (Also, it's quite interesting that I typed 'turdle' before correcting myself with 'turtle'). But, most of all, I love that she said, "I'm turd" and persisted with her sentence despite the fact that I was laughing uncontrollably. Incidentally, Jill also faces a prospect discussed late in this lecture. That was a teaser, to try to intice you to listen to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment