This year, when I get a moment, I'm usually feeding the baby and so I don't have two hands and have found trying to read a book awkward. So I've been reading copious amounts of non-fiction on my phone, rather than books. The one book I read when I have some quiet and two hands to gently hold it is the Codex Seraphinianius, written and illustrated by Italian architect Luigi Serafini from 1976 to 1978. It's a visual encyclopedia, of a foreign, paradoxical yet familiar, world, complete with its own language and obscure meanings. I've written about it and alluded to it previous to ever seeing a copy in person, a few times, in fact. An original first edition will run you about $5000, but a new edition came out last year, for a much more conceivable $200 for a large, beautiful, hardcover book. It comes complete with a new preface by the author, which I enjoyed. He describes how he made the book - the physical process - without destroying the beauty of the unknown why or what it really is about. He basically writes (and I should perhaps post a spoiler alert for the purist), I don't know, I was somehow compelled, maybe that weird stray cat 'dictated' the Codex to me? RJH gave it to me for Christmas. Wanting to get back into writing reviews of what I read (in the most generous sense of the word), I've been thinking about how one could review a mysterious tome, all alien illustrations and imagined alphabet or syllabary and language.

It occurred to me the best way would be something like this.

1. Codex Seraphinianius, written and illustrated Luigi Serafini.

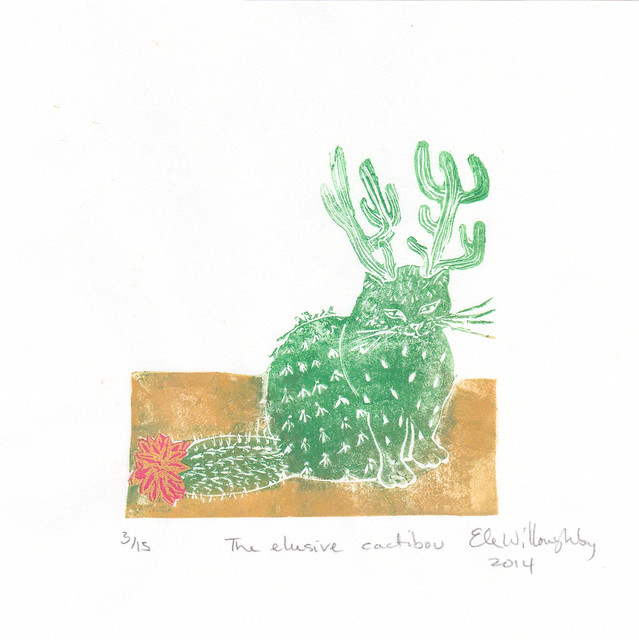

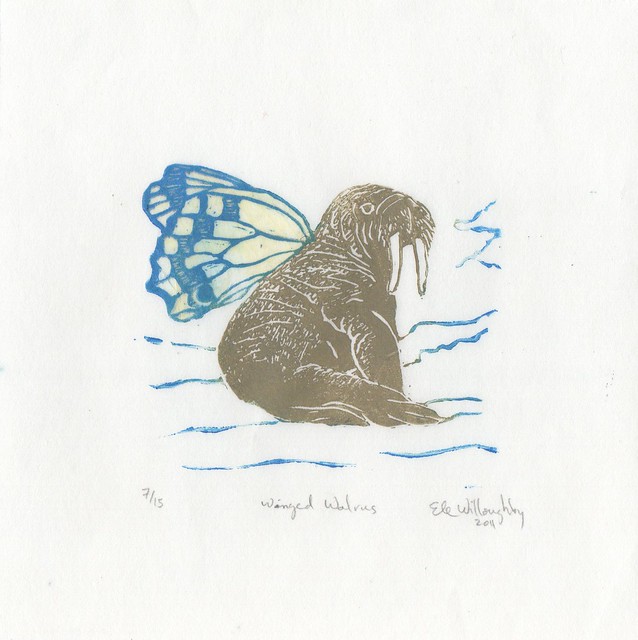

I mean, it's sort of obvious in hindsight, no? What can one say to the Codex, but to reply in kind with an illustration of a bizarre, unknown creature, which nonetheless seems to be built of familiar parts (say, a cat, cacti and caribou antlers) and its own internal logic? No sooner had this idea had entered my mind than it grew into a series of mini print illustrations of fantastical creatures, beginning with my previous mini print, the winged walrus.

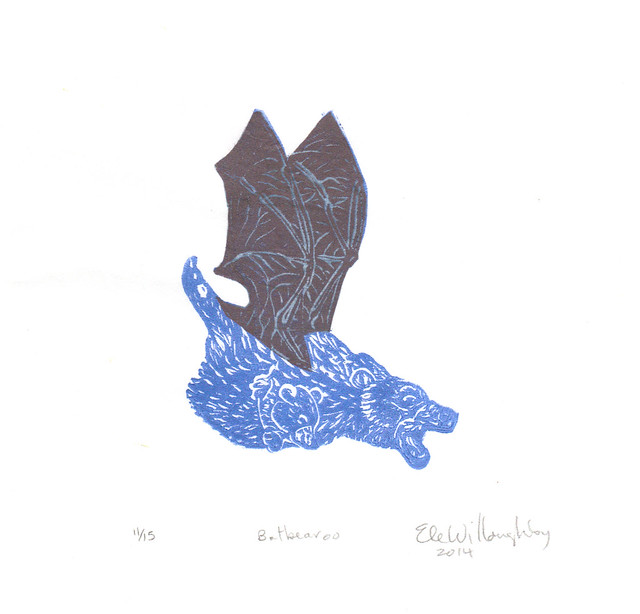

And before long, I needed to make a print of the Batbearoo (neither bat, nor bear, but a flying marsupial).

Anatomie Et Biologie Des Rhinogrades — Un Nouvel Ordre De Mammifères, Masson, France (1962) is the most wonderful sort of fictional science (rather than traditional science fiction). The original was published in German as Bau und Leben der Rhinogradentia in 1957. There exists an English translation by Leigh Chadwick in 1967 called The Snouters: Form and Life of the Rhinogrades, but I've only found my French edition. Stümpke created an entire new (imaginary) order of mammals, the rhinogrades (or "snouters") whose most remarkable characteristic was the nasorium, an organ derived from the ancestral species' nose, which had variously evolved to fulfill every conceivable function, notably including locomotion. It's written much like a regular scientific treatise, complete with footnotes, references, Latin species information and a straight face. He never actually says anything to suggest that this order of mammals, or their home the Hi-Yi-Yi Pacific Islands are anything other than real. As I explain here, this 'scientific' text is truly magical, and I even cried at the end. It is understandably a great favorite amongst zoologists.

I was reminded of a couple of my other favorites. Harald Stümpke's

The other favorite is "The Book of Imaginary Beings" by Jorge Luis Borges with (poor forgotten) Margarita Guerrero (who is often omitted from the author list), which I did review here. It's another sort of imaginary encyclopedia of sorts, though written in human languages (Spanish, and readily available in English translation). It's a miscellany of the marvellous, written in Borges' typical magical scholarly fashion.

It's possible I have also been influenced by reading my tiny son Mercer Mayer's Little Monster's Bedtime Book several times. It's a lovely little illustrated storybook of 15 poems about monsters he invented - and, importantly, defined and described, published when I was but a wee little thing myself.

It occurred to me that there is in fact an entire proud tradition of these sorts of scholarly or scientific treatises on the not quite real, masquerading as fact. You might consider the 15th century Voynich manuscript, to which the Codex is often compared. It too is written in an unknown script, appears to be a sort of illustrated encyclopedia, or possibly nonsense. It has long intrigued scholars. Just last year, an article on a new study, published in the journal PLoS One, argued that the manuscript has a real, decipherable message (as reported by the BBC here). A large portion of the what I think of as 'proto-science', both intentionally (usually to confuse competitors, if one was say an alchemist) or unintentionally fall into this category. During the classical advent of history, Herodotus and Pliny for instance, did not really distinguish between "I can attest that this is factual" and "some guy told me this half-baked story over beers". Or, at least, it's fair to say they compiled their works in the absence of modern methods to try and establish the veracity of natural history of any sort.

So my next project is clear. These works have given me so much pleasure, I need to write my own fictional zoological text, featuring the likes of the winged walrus, batbearoo and cactibou! I plan a collection of mini prints, along with pseudo-zoological descriptions of these rare (and you know, possibly imaginary) creatures. After all, I think of much of my work as a sort of wunderkammer, and a true cabinet of curiosity is not just group of specimen of natural history both real and imaginary, but a proper collection, of ordered, organized and described things, in its own proto(pseudo)-scientific fashion.

No comments:

Post a Comment