|

| Mary Somerville, linocut print 11" x 14" by Ele Willoughby, 2019 |

After her year of schooling she did spend a lot of time reading, or resentfully working on a sampler, stitching letters and numbers. Her aunt Janet disapproved of her reading and neglecting her poor sewing skills and she was sent to the village school for needlework lessons. The village school master began to visit in the evenings and teacher a bit more including how to use a globe. When she was 13 she was sent to writing school in Edinburgh during the winter months, where she finally learned arithmetic. She taught herself enough Latin to read books in their home. She confessed this to her favourite uncle Dr. Thomas Somerville, the adult in her life who didn't discourage her pursuit of ideas and learning. He told her women had been scholars even in ancient times and read her Virgil to help her learn more Latin. She went to visit her uncle William Charters, in Edinburgh, where she was sent to dancing school to learn manners and to curtsey. She also met the Lyell family, befriending Charles, who would go on to revolutionize geology.

Mary stumbled upon mathematics unexpectedly. A young woman, whom she met when dragged to a tea party by her mother, invited her to come see her needlework and showed her a ladies' magazine with puzzles. Mary was fascinated by the mathematical puzzles and solutions the magazine published. Her new friend could only tell her these were called algebra. She sought books at home to help her decipher this but she only found a book on navigation. It did not help with algebra, but she was introduced to trigonometry and learned there was more to astronomy than stargazing. She asked her younger brother's tutor to buy her an algebra textbook and Euclid's Elements, and soon she was staying up late to read these after chores. But she ran through too many candles and her parents put a stop to this, fearing for her sanity; they like many contemporaries felt that higher learning was unnatural in a woman. She continued to study in secret.

Nicknamed "the Rose of Jedburgh" among Edinburgh socialites, her expected role was to marry and so she did. She married her distant cousin Samuel Grieg, a commissioner in the Russian navy and London-based Russian consul. They were not a good match. He held a low opinion of the abilities of women and no interest in science. Left largely alone, she began to study French and more mathematics. She was widowed within three years and left with her young toddler son Woronzow, a baby, and a small inheritance. She returned to live her parents, more independent now as a widow.

|

| Laplace's Demon, by Ele Willoughby 2011 |

She had studied plane and spherical trigonometry, conic sections and James Ferguson's Astronomy. Despite her children and household chores she ambitiously tried to read Newton's Principia. She met intellectuals like Lord Henry Brougham, and the renown Professor of mathematics and natural history, John Playfair who encouraged her mathematical studies and introduced her to mathematician and astronomer William Wallace. She corresponded with Wallace about her mathematical problems. She made a name for herself when she was awarded a silver medal in 1811 by solving a mathematical problem posed in the mathematical journal of the Military College at Marlow. Wallace suggested she read mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace on gravity and all physics in the decades since the Principia first appeared in 1687. Finding she understood Laplace's five-volume Mécanique Céleste (Celestial Mechanics) as well as the tutor she hired, her confidence increased, and she expanded her studies to astronomy, chemistry, geography, microscopy, electricity and magnetism, buying a "excellent little library" of math and science books at the age of 33. She began to see that English mathematics, dominated by Newton, had stagnated and fallen behind their continental colleagues, by not adopting Leibnizian calculus.

William Somerville (1771–1860). He was inspector of the Army Medical Board, and the son of her favourite aunt and uncle. Elected a member of the Royal Society, William Somerville socialized with leading intellectuals, scientists and writers of the day and was a devoted supporter of Mary's studies. She returned to reading Laplace and Newton after their honeymoon. The family (including William's illegitimate son who became close with Woronzow) moved to Hanover Square into a government house in Chelsea when William was appointed to the Chelsea Hospital in 1819. Her marriage was a very happy one, though they had a disastrous financial loss (the trusting William acted as guarantor for a relative's loan) and were devastated by the early death of three of Mary's six children; her second son from her first marriage died at nine, her first son with William died as a baby, and their first daughter Margaret died at ten. Woronzow, and their daughters Martha and Mary survived.

|

| Caroline Herschel, linocut by Ele Willoughby, 2014 |

|

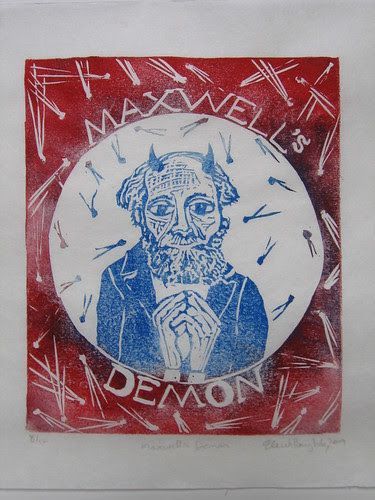

| Maxwell's Demon, linocut by Ele Willoughby |

Mary began experimenting and published her first paper on "The magnetic properties of the violet rays of the solar spectrum", in the Proceedings of the Royal Society in 1826. Her results were praised and reproduced by others but ultimately shown to be incorrect, which crushed her confidence in performing her own experiments. The truth is that finding small errors in experimental design and correcting and improving them is part of the normal process of science. She was the first woman to publish scientific results under her own name. Had she not been a woman and an outsider, she might have realized she had no reason to feel embarrassed. In 1829, Sir David Brewster, inventor of the kaleidoscope, wrote that Mary Somerville was "certainly the most extraordinary woman in Europe - a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman".

|

| Antoine et Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier, linocut with collaged washi, 2018 by Ele Willoughby |

Her next book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences (1834) was even grander in scope, connecting and summarizing the physical sciences of physics and astronomy with geography and meteorology. This book sold 15,000 copies establishing her reputation as amongst the elite of scientific authors. It was her publisher John Murray's most successful science book until Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859. The book went through nine editions and she updated it for the rest of her life, even pointing out in the third edition that the challenges in calculating the position of Uranus hinted at the existence of further possible undiscovered planets. She wrote that perhaps even the mass and orbit of this hypothetical planet could be deduced from observations of Uranus. Somerville's insight inspired British astronomer John Couch Adams who was able to mathematically predict the existence of Neptune in 1846. In his review of Connexion, polymath William Whewell introduced (for the first time in print) a new term he coined three years prior: 'scientist.' Many claim he praised her as the first scientist, but while he praised her text as "masterly" and praised her rare skill at mathematics, he did not apply the work scientist to any individual.

Though she had many male scientist friends and mentors, as a woman she was usually barred from scientific societies. Her husband presented her papers to the Royal Society on her behalf, as did John Herschel. Their friend Arago presented her results on light and chemistry to the French Academy of Science. Faraday praised her explanations of his work, which was cutting edge research at the time of the publication of Connexion. Throughout her career, she had great instincts and open-mindedness about new ideas. She supported her friend Thomas Young's controversial wave theory of light, a real paradigm shift. Young explained his famous double-slit experiment by building on his French friend Augustin-Jean Fresnel's explanation of the diffraction of light in terms of waves and Christian Huygen's idea of the propagation of wavefronts of light, at a time when Biot and Laplace were still expounding on the particle nature of light. Likewise, she hinted at the revolution to come with the next generation of physicists who showed how seemingly disparate forces could be combined. Mary wrote, "Various circumstances render it more than probable that, like light and heat, [electricity] is a modification or vibration of that subtle ethereal medium, which, in a highly elastic state, pervades all space," which inspired the subsequent investigations by Hans Christian Ørsted (also written Oersted) and Michael Faraday. Mary noted that mariners observe lightening affects compasses. She described American John Henry's electromagnet, able to hold a ton of metal. And she traced the history of electrical and magnetic investigations since Coulomb. Later, the great physicist James Clerk Maxwell who combined the forces of electricity and magnetism in his laws for light, cited Somerville's book On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences for its hints of connections between light and magnetism, electricity and light, colour, electricity and magnetism and heat. He praised her insight and took the time to carefully explain why her experiment using violet light to magnetize a needle had failed. Mary may not have succeeded in establishing the connection between light and magnetism, but in searching for it she was on the vanguard of contemporary research.

In 1848 she published her most popular book, Physical Geography, which was the first textbook on the subject in English. It went through six editions in her lifetime, was used until the early 20th century and won her the Victoria Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society in 1869. Physical Geography was influential, ignoring political divisions and viewing humanity as a part of nature, but a part able to affect its environment, emphasizing interconnectedness and interdependencies. While she was working on this book, she was initially discouraged by German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt’s publication of his first volume of Kosmos (1845), which covered similar subject matter but John Hershel encouraged her to continue and as she wrote, follow "the noble example of Baron Humboldt, the patriarch of physical geography." She takes her readers through the place of the Earth in the solar system, its structure, features of land and water, formation of mountains, volcanoes, oceans, lakes and rivers, and what impacts temperature, electricity, magnetism and the auroras before turning to the distribution of life. Impressed, Humboldt himself wrote to her, "You alone could provide your literature with an original cosmological work." Her book also precipitated some backlash because her discussion of geology contradicted the biblical estimate of the age of the Earth, but she wrote, "facts are such stubborn things." Four years later, the Somerville family, Mary and William and their daughters Martha and Mary, moved to Italy for health reasons and because the cost of living was lower.

William Somerville died at 89 in 1860 and then her son Woronzow died suddenly, at age 60, in 1865, sending Mary into a deep grieving period. So when Maxwell published his theory of electromagnetism in 1865, Mary was preoccupied with grieving and took little notice of this monumental work she helped presage and inspire. Now in her 80s, she began work on her memoir. Mary had always put her fame and scientific credibility to work to support causes she believed in, including women’s suffrage, arguing that science was too often used for military purposes, the antivivisection movement and drawing attention to the way human activity was causing animal extinctions. A lifelong lover of birds, she had a pet mountain sparrow which would sleep on her arm as she wrote. She noted the decline in "feathered tribes" of Europe who would be "avenged by the insects." In 1866 when philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill organized a massive petition to Parliament to give women the right to vote, he asked Mary Somerville to be the first to sign. She was a member of the General Committee for Woman Suffrage in London, and petitioned London University unsuccessfully to grant degrees to women (noting that in France, Emma Chenu had been granted an MA in mathematics and a Russian lady, likely Sofia Kovalevski, had also taken a degree). She viewed her final book as a mistake. Published at age 88 in 1869, On Molecular and Microscopic Science, a popularization of science book, it was not as well received as her previous works, but was nonetheless sold well. She explained the latest thinking on atoms and molecules and revealed the lifeforms discovered with the microscope. But, she felt her time would have been better used if devoted more purely to mathematics, and began working to catch up on the latest mathematics research and returned to work on her 246-page manuscript on curves and surfaces. She enjoyed her old age and was glad to keep her faculties, work on mathematics and take an interest in current affairs until her own death, expressing only regret that she would not live to see results of scientific expeditions underway or the abolition of the slave trade. She died on November 28, 1872, while working on a mathematical paper on Hamilton's quaternions, approaching her 92nd birthday. Her obituary in The Morning Post read, "Whatever difficulty we might experience in the middle of the nineteenth century in choosing a king of science, there could be no question whatever as to the queen of science." Her daughter Martha edited her autobiography, Personal Recollections, from Early Life to Old Age (1873), and it was published posthumously.

In my portrait, I've shown Somerville with diagrams from her first two books, emphasizing the importance of her impact on astronomy and physics, and highlighting some of the cutting edge science she presented (like connections between electricity and magnetism, and Young's Double Slit Experiment).

References

Mary Somerville, Mechanism of the Heavens, London: John Murray 1831

Mary Somerville, On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, London: John Murray 1834

Mary Somerville, PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS FROM EARLY LIFE TO OLD AGE OF MARY SOMERVILLE WITH Selections from her Correspondence BY HER DAUGHTER, MARTHA SOMERVILLE. London: John Murray, 1874

Robyn Arianrhod, Seduced by Logic: Émilie du Châtelet, Mary Somerville and the Newtonian Revolution, OUP, New York, 2012

James Secord, 'Mary Somerville's Vision of Science' Physics Today 71, 1, 46 (2018); doi: 10.1063/PT.3.3817

'Mary Somerville', Britanica, accessed November 2019

Mary Sommerville, Wikipedia, accessed November 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment