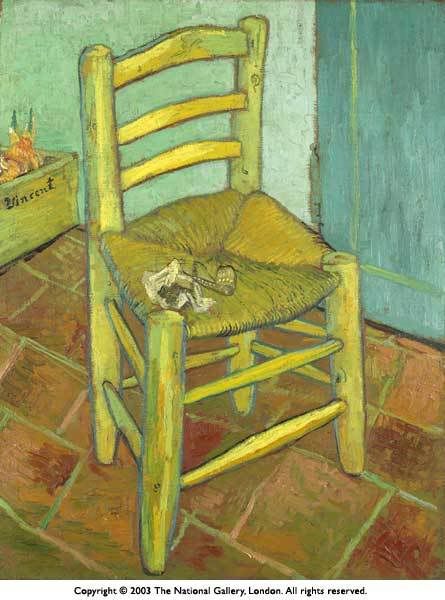

13. A. S. Byatt Still Life. This is the second book in the quartet, which started with The Virgin in the Garden, the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and harkening back to Queen Elizabeth I, which I read some time ago. I don't think I realized at the time that it was one of four. But, there are the characters, the Potter family, strangely still living in 1954 in England, where I left them. Frederica is still as cursed with intelligence, red hair, and little sense of the interior life of others; she goes off to Cambridge, of course, and continues to fall in love with impossible men. Stephanie starts her more docile, womanly life as wife and mother to Vicar Daniel. Marcus is recovering from his bizarre folie à deux and the strain of living with his angry, demanding, atheist father Bill. He is living with Stephanie and Daniel, and Daniel's horrible mother. Mother Winnifred is left alone in the house with Bill. Alexander is trying to follow up his play Astraea, and his writing about Vincent Van Gogh, and his relationship with Gaugain and his letters to Theo. His new play is The Yellow Chair. The staging involves the two paintings above, of Vincent's own chair and the chair of Gaugain. Many secondary characters are there too, including Wilkie and the Pooles and so on.

The story is compelling. The characters are real and full. She manages to evoke the time and place and its conventions and culture. To the point, for instance, that she made me angry at the way pregnant women in Yorkshire, in 1954 were treated like cattle, herded from waiting room, to hallway, to waiting room, without so much thought as to provide sufficient chairs. The prose however, feels dense and abstruse, in a way which differs from later novels. I found myself reading and rereading sentences thrice to try and glean their meaning. I have really enjoyed the way she weaves in allusions to other literature, say in Possession. Here it seems almost too academic, occasionally like a novel for people who read English at Cambridge in the 50s - a rather limitted audience. I am glad at least that I have read Lucky Jim, thanks to

Sociologically, it is very interesting to see how these people lived their lives. We tend to think of the 50s as sort of innocent and sheltered. Though the people are English - uncomplaining, reserved, polite - they are anything but innocent or frigid. Frederica of course, lives life to the fullest, and goes through quite the collection of men. At Cambridge they outnumber the women eleven to one. These characters are memorable, especially her Scottish cameleon friend Alan. Also the household in which Alexander lands, living with Thomas and Elinor Poole and their three children in London, while he writes his play, is certainly a fascinating arrangement.

She also breaks your suspension of disbelief sporadically by commenting on her own goals as novelist, or revealing the image in her mind which inspired the novel. She discusses how she planned initially to write a novel without metaphors, a particularly odd goal for her it seems to me. She quickly gave up this plan, and resorts instead to simply discussing it with the reader directly. She writes about her process and what happens in the minds of readers. Today this seems a bit self-consciously post-modern. However, she does seem to convey that the characters are none the less real, as if they were people, who lived their lives, and she just came along and wrote about these particular lives, to reach her stated goals, to look at the lives, particularly of women in England in the 50s, and the meaning and role of metaphor.

Not an easy read. Perhaps I needn't worry so much about the details. But, I will say, that I intend to read the remaining two novels in this series. I want to know what happens to these people. I do feel invested in their lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment