|

| Hildegard von Bingen, linocut, 11" x 14" by Ele Willoughby, 2023 |

It is once again Ada Lovelace Day, the 15th annual international

day of blogging to celebrate the achievements of women in technology,

science and math, Ada Lovelace Day 2023 (ALD23). I'm sure you'll all recall, Ada, brilliant proto-software engineer, daughter of absentee father, the mad, bad, and dangerous to know, Lord Byron, she was able to describe and conceptualize software for Charles Babbage's

computing engine, before the concepts of software, hardware, or even

Babbage's own machine existed! She foresaw that computers would be

useful for more than mere number-crunching. For this she is rightly

recognized as visionary - at least by those of us who know who she was.

She figured out how to compute Bernouilli numbers with a Babbage analytical engine. Tragically, she died at only 36. Today, in Ada's name, people around the world are blogging.

Despite some biased ideas about the Medieval period, which we inherited from Enlightenment scholars, the Dark Ages were only "dark" in the sense that there is a dearth of documentation. All too often, people have the idea that this was a stagnant period in the pursuit of knowledge after the end of the Classical period. Many documents of the time have simply been lost, so we don't have a lot of information about many individuals and their specific advancements in scientific thought. But the sheer fame and productivity of Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) is an exception. Her writings preserve not only her own knowledge and theories but much of the nature of institutional medicine and folk healing of her day (which she deftly combined). While she might be best remembered today as a composer of seventy Gregorian chants and musical dramas and as a Catholic saint, author of biblical commentaries, three books on her visions and two biographies, she is also recognized as the progenitor of natural history in German-speaking lands and author of medical and natural history texts. She even invented her own script and language!

Likely born the tenth child in her rural Rhineland family, her religious parents raised her intending for her to be a tithe to the church, and she entered the double-monastery at Disibodenberg at 14. Her well-respected magistra Jutta (1092-1136) became her mentor and teacher, and it is believed Hildegard was assigned to the infirmary. There she would have been responsible for, in particular, for but likely not limited to, the health of the women at the monastery and adjoining community. She would also have had access to the books and knowledge of her male counterpart, who was responsible in particular for the health of the men. After Jutta's death, Hildegard was elected magistra and she lead the Disibodenberg nuns until 1148, when at age 50, inspired by a vision, she moved them all to a new monastery at Rupertsberg at Bingen. She immediately began writing her text books. Physica describes elements, mammals, reptiles, fish, birds, trees,

metals, and precious stones and medicinal uses of 293 plants (230 herbaceous plants and 63

trees). Causae et curae was written presumably to ensure that her replacement in the infirmary had all the knowledge she would need. It describes 47 diseases along with causes, symptoms and treatments and goes on to document 300 plants used to treat diseases. It reads both like a Medieval first aid manual and technical scientific writing of her day. She lived in the new monastery until her death at 81. People traveled to Rupertsberg to receive healing from Hildegard and her order. She was a prodigious correspondent and has been called a Medieval

"Dear Abby" because of her letters to such luminaries as King Henry

II of England, King Louis VII of France, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederic

I Barbarossa, the Byzantine Empress Agnes of France, Bernard of Clairvaux, four popes and others. She was invited to preach at nearby cathedrals including at Cologne, Mainz and Worms. By the time she reached 80, she was so respected and renown that she could defy the pope and it was the pope who had to back down. Commanded to excommunicate a man in her community, she simply declined to do so.

Outside of Salerno, those practicing medicine in her day were not university educated, but either working in monasteries and infirmaries or were folk healers using herbal folklore. Hildegard's contemporary woman in medicine Trota of Salerno is a notable exception, as she was formally educated at the medical school in Salerno. The rise of universities and formal medical schools actually lead to greater exclusion of women from medical practice; universities usually excluded women.

Hildegard developed a holistic understanding of medicine and was systematic and scientific in her approach within her Christian worldview. She is believed to have access to ancient Greco-Roman medical sources, typically available and shared between monasteries, including the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Pendanius Dioscoride. The Classical humoural theory was central to medicine until the 17th century. It related humours, or the vital bodily fluids, namely, according to Hipocrates, the blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile to human health and behaviour. Blood was considered hot and wet, yellow bile hot and dry, black bile cold and dry and phlegm cold and wet; these properties were used to try and diagnose how these humours might be unbalanced and causing disease. She likely also had access to texts by pioneering Arab and Persian physicians, and was abreast of some of the contemporary advancements from the Salerno school of medicine. Her medical philosophy is influenced by St. Augustine, Isidore Hispalensis,

Bernard Sylvestris of Tours, and perhaps Boethius. She would have been trained in nursing, diagnosis, prognosis, pharmacy and treatment by her monk colleague in the infirmary at Disibodenberg. She herself wrote about how the infirmarian was responsible for the infirmary garden and the "spices and medicinally active herbs," thus, she became expert at gardening and botany too. In addition to Latin terms, Hildegard includes German names for plants she could not name in Latin, so scholars believe she also incorporated knowledge from the folk herbalist, magical and medical tradition. Some instructions even prescribed charms and incantations. Importantly, she synthesized these disparate sources of knowledge. Along with the humoural theory, she believed that everything on Earth was made by God for man, so there's very little which could not be used in medicine to counter a humoural imbalance. For instance, she prescribed a poultice of quince, deemed "dry" to treat the "dampness" of an ulcer. Her writings actually allow an unusual insight into "wise woman" healing practices, as it was rare for other women to be literate in Latin. She wrote that she was told to ‘write down that which you see and hear’ in a vision, and thus recorded her visions. But she takes the same approach with medicine, writing down observations and supplementing her observations with knowledge from books rather than simply relying on their authority. This strategy hints at the beginnings of the scientific method.

Her philosophy of medicine was deeply influenced by her experience in the garden and she gives a special focus on "viriditas" or the greening power of plants, expanding on Galen and Hippocrates' four humors, connecting plants to human health, and viewing this greening force as also vital within the human body. She ties viriditas directly to fertility and vigor and describes it as a humour that can dry up. She approaches medicine the way a gardener nurtures a garden. Her approach in all things was quite holistic and she believed spiritual health complemented physical health. She begins her text Causae et curae with the creation of the cosmos and connects the human person as microcosm to the sacred macrocosm of the cosmos. Her work documents causes of disease, sexuality, psychology, physiology, diagnosis, treatments and prognosis. Illness, she wrote, was a result of falling into disharmony with creation and could be treated with rest, herbal cures, steam baths, a proper diet, and achieving spiritual peace. Her goal was to heal body, spirit and mind; in the 12th century healers commonly viewed health as involving all of these things.

She discussed sexuality openly and women's reproductive health. She described female orgasm, nocturnal ejaculation, coitus as therapy, conception, birth, complications in childbirth, gynecological diseases, menstruation (including botanical emmenagogues or menstruation stimulators), abortifacients (substances which can induce an abortion including sarum, white hellebore, feverfew, tansy, oleaster, and farn) and menopause. Medieval Christian healers would not hesitate to proscribe abortifacients to save a mother's life if it were at risk. She wrote about determining an embryo's sex and noted that children need affection for their psychological development, writing “The strength of the male seed determines the

sex of the embryo, while the love of one parent to the other determines

the moral qualities of the child.” She is likely the first woman to write about skin diseases and treatments including leprosy, scabies, lice, insect bites, burns and conditions now believed to be erysipela, paronychia, contact allergies, rosacea,

and rhinophyma. Hers is the first description of a peeling for rosacea, a method still used; she used plants that promote

blistering on the skin, which would then rapidly heal. She recommended skin treatments with plants which we now can confirm have anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. She recommended a balanced diet including cutting back on food high in fats and cholesterol and that salt should be taken in moderation to avoid hypertension. She writes about kidney and liver ailments and treatments; in her day, uroscopy and examining urine was considered a doctor or healer's most reliable tool. She herself suffered migraines and she wrote about headaches and remedies. She precisely described toothache and even how nerves run from the brain to gums and the need for dental hygiene. She addresses depression, anxiety and schizophrenia. A modern study investigated whether her correct herbal remedies were mere lucky strikes - that is whether herbal remedies she reports which are still supported by modern science are just a result of chance. They found this could not be the case. Though most of her claims are not correct, she is correct far too often for it to be by mere chance. Further, she does not repeat all claims in ancient sources, suggesting she was independent in her thinking. Most of her remedies are ingredients from the kitchen or garden but she also recommends the use of minerals including gold

for arthritis, emerald for heart pain, jasper for hay fever or for

cardiac arrhythmia, gold topaz for loss of vision, sulfur ointment for scabies and blue sapphire for

eye inflammation; most of these play no role in modern medicine, though gold is still used for arthritis and sulfur is still used for skin treatments for people and domestic animals. While all her writings and worldview were firmly planted within her faith, she did not presume sin was the primary cause for disease; bad humours, bad lifestyle or the weather were more often suspected. She makes pragmatic practical suggestions rather than trying to treat illness with prayer, penitence or pilgramage.

She invented her own alternate alphabet or secret code with symbols for each letter and applied it to her own Lingua ignota (Unknown Language), which consisted of 1000 invented words for a list of nouns. Scholars are divided on her intentions; was this a secret language to increase solidarity within nuns in her order, or was this intended for anyone? Modern conlangers (aficionados of constructed languages) view her as a Medieval precursor.

She formed a deep friendship and love for her assistant Richardis von Stade, who worked beside her on her major work Scivias. When Ricardis was elected abbess of a

monastery at Bassum, far from Rupertsberg in 1151, Hildegard was bereft. She wrote to Richardis' mother, to the Archbishop of Bremen and even to the pope, trying to get them to intervene, to no avail. She wrote letters of her grief to Ricardis, writing "Now, let all who have grief like

mine mourn with me, all who, in the love of God, have had such great

love in their hearts and minds for a person- as I had for you- but who

was snatched away from them in an instant, as you were from me." Tragically, Richardis died the next year.

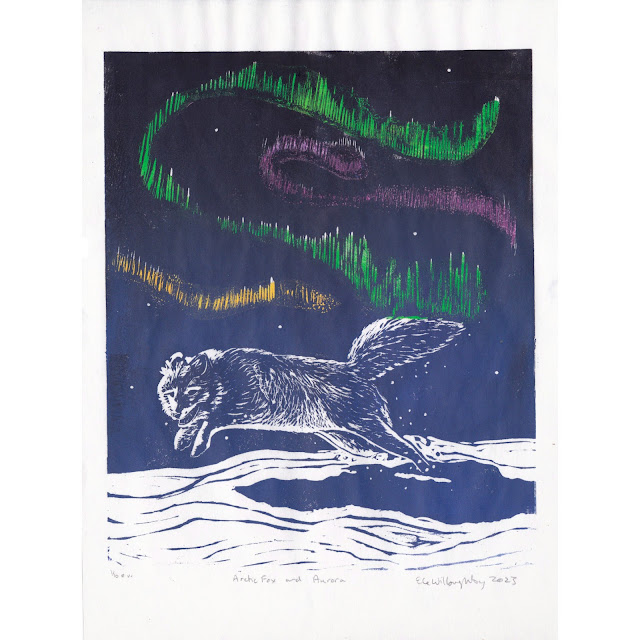

My portrait includes some of her prescribed treatments which we can now confirm do have medical benefits (or at least effects). Clockwise from the top, she is surrounded: by tansy (Tanacetum vulgare) which has antibacterial and toxic contents; common comfrey (Symphytum officinale) is sometimes used on the skin to

treat wounds and reduce inflammation from sprains and broken bones, it roots and leaves contain allantoin, a substance that helps new

skin cells grow, along with other substances that reduce inflammation

and keep skin healthy; mandrake (species in the genus Mandragora, either Mandragora officinarum or Mandragora autumnalis) which contain hallucinogenic tropane alkaloids which are poisonous; sulfur she prescribed for skin ailments does indeed act as a fungicide; lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) which has been shown to have some calming effects, some antibacterial properties and positive effects on indigestion; and quince (Cydonia oblonga), which is understudied, but there is some early evidence that it may help prevent stomach ulcers (which would actually coincide with her advice).

Above and below Hildegard is the alphabet along with her own alternate alphabet Litterae ignotae which she used for her own Lingua ignota (Unknown Language). The scroll in her hand also shows medieval musical notation to represent her compositions.

Her map of the universe from her book Scivias in illustrated on her habit. She correctly viewed the Earth as spherical, and then in the typical Medieval worldview, she posits a series of concentric celestial spheres, influencing events on Earth. Other Medieval thinkers describe a spherical universe. The shape of Hildegard's map of the universe is unique; some describe it as oval, or egg-shaped others, more directly, as vulva-shaped. In the centre of her diagram is the Earth, as as you move upward, you see the moon, then the inner planets Mercury and Venus (which look like stars), then beyond the ring there is the Sun (the large flower-like shape) and outer planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn (the three outermost star shapes). Recall, the further planets are not visible to the naked eye. She wrongly assumes the antipodes are uninhabitable, without a more modern understating of the cause of the seasons. Seasonal variations in the heavens and seasons on Earth were attributed to winds.

While you could not call a Medieval woman a feminist, she did believe that men and women were equal before God, and rejected the prevailing Aristotelian idea that women were inferior inversions of men, with opposite but inferior relationships with humors and elements. She wrote, rather that, that women had different but not opposite or inferior relationships to the elements. To her, men and women were complimentary aspects of the

divine.

Hildegard entered the monastery an uneducated child and grew to be a renown, respected thinker and healer, with a tremendous output in music, theology, natural history and medicine, who has been recognized as a saint. Her writings on medicine and reputation as a healer were used as arguments by early feminists that women should be admitted to medical schools. Her music has seen a resurgence of interest. Her impact and influence can still be felt today.

* Offering the tenth child as a tithe to the church was a common practice, and many scholars believe Hildegard was the tenth child in her family, but we lack surviving documentation of 9 older siblings, so we can't state this with complete certainty.

Sources

Brady, Erika. Healing Logics: Culture and Medicine in Modern Health Belief Systems. 1 ed. Utah State University Press, 2001. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/9398.

Janega, Eleanor, Going Medieval blog, posts tagged 'Hildegard of Bingen,' accessed October, 2023.

Hay, K.A., "Hildegard's Medicine: A Systematic Science of Medieval Europe." Proceedings of the 17th Annual History of Medicine Days, March 7th and 8th, 2008, Heath Science Centre, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/47483 Downloaded from PRISM Repository, University of Calgary

Hildegard of Bingen, Wikipedia, accessed October, 2023

Johnston, Sophie., Hildegard of Bingen, Bluestocking Online Journal of Women's History, January 1, 2008.

Lockett, Charles J., Was Hildegard von Bingen the First Medieval Scientist? Medieval Blog, July 18, 2022

The Medieval Garden Enclosed, posts tagged 'Hildegard of Bingen', The Metropolitan Museum of Art blog, accessed October, 2023.

Mount Sinai Health Library, accessed October, 2023.

Sharratt, Mary, "Hildegard the Healer," on Feminism and Religion, May 13, 2015.

Singer, Charles. 'The Scientific Views and Visions of Saint Hildegard (1098-1180)', in Studies in the History and Method of Science, edited by Charles Singer, Oxford at the Claredon Press, 1917.

Stefanidis, Ioannis, Theodoros Eleftheriadis, Maria Efthymiadi, Maria Kalientzidou, and Elias Valiakos, Remedies for Kidney Ailments in Physica by Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), Volume: 21 Issue: 6 June 2023 - Supplement - 2, Pages: 53 - 56, June 2023.

Sweet, Victoria, 'Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine', Bulletin of the History of Medicine , Fall 1999, Vol. 73, No. 3 (Fall 1999), pp. 381-403 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44445287

Ramos-e-Silva, Marcia., Saint Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179): “the light of her people

and of her time”. International Journal of Dermatology 1999;

38(4):315-320.

Uehleke, Bernhard, Werner Hopfenmueller, Rainer Stange and Reinhard Saller, Are the Correct Herbal Claims by Hildegard von Bingen Only Lucky Strikes? A New Statistical Approach. Complementary Medicine Research Forschende Komplementärmedizin / Research in Complementary Medicine (2012) 19 (4): 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341548 Published Online: 01 April 2012