|

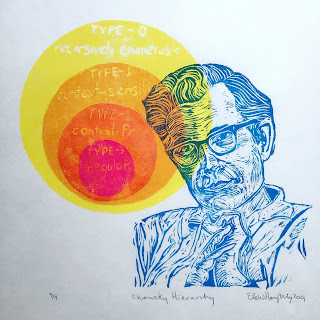

| Marie Maynard Daly, linocut 9.25" x 12.5" by Ele Willoughby, 2021 |

This is a hand-carved and hand-printed linocut portrait of trailblazing American biochemist Marie Maynard Daly (1921-2003). Daly, the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry in the US, made important research contributions to our understanding of the biochemistry of the cell nucleus and cardiovascular issues. Her interest in the nuclear proteins within cells lead to important contributions to our knowledge of the chemistry of histones and protein synthesis. She published original research establishing that "no bases other than adenine, guanine, thymine, and cytosine were present in appreciable amounts" in DNA - research which was cited when Watson and Crick accepted the Nobel Prize for the structure of DNA. She did some of the earliest work on the relationship between diet and cardiovascular health. She was the first to show how cholesterol could clog arteries and that hypertension lead to atherosclerosis; these were invaluable discoveries in our understanding of heart attacks and work to lower the risk of heart attacks. She also did early work linking smoking and hypertension. Later she made studies of the uptake of creatine by muscle cells, which is important to understanding the recycling systems of muscles. She did this at a time when there where tremendous barriers due to race and gender discrimination in fields of research where women and minorities are still underrepresented.

Born April 16, 1921, in Queens, NY, she was the eldest of three and had twin younger brothers. Her father Ivan Daly was an immigrant from the British West Indies who had come to the US on a scholarship to Cornell to pursue his own dream of a career in chemistry, but when he and his family were unable to cover the tuition and board, he had to drop out of school. He supported his family as a postal worker, and passed on his love of science to his children. Her mother Helen Page Daly was a homemaker, avid reader and fellow lover of science, who also fostered her children's education. Marie's grandparents had a library with many biographies of scientists. Marie recalled being fascinated as a child by Paul DeKruip’s Microbe Hunters, with its stories of scientists like van Leeuwenhoek, Pasteur and Koch and being encouraged in her interests by parents and teachers alike. After attending an all-girls high school in Manhattan, she won a scholarship to Queens College. She could remain close to home, and save money living at home. She graduated magna cum laude with a BSc in chemistry in 1942, in the top 2.5% of students, a Queens College Scholar and inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa and Sigma Xi honor societies.

She got lab and teaching assistant jobs at Queens College to support herself as she continued on, studying for her Master's at New York University, and afterwards. As WWII raged, and employment opportunities for a Black woman in chemistry were uncertain, she decided her best bet was to continue her education, and she began doctoral studies in biochemistry at Columbia under Dr. Mary Letitia Caldwell, Columbia's first female chemistry professor, a well-known expert in enzymes and nutritional chemistry. She graduated only three years after enrolling, in 1947, with her thesis "A Study of the Products Formed by the Action of Pancreatic Amylase on Corn Starch," unaware that she had become the first Black woman to earn a chemistry PhD, at a time when only 2% of Black women had college degrees. She was the first Black person to earn a doctorate from Columbia.

She wanted to work with biochemist Dr. Alfred Ezra Mirsky (one of the first to isolate mammal messenger RNA) but he told her she would need to provide her own funding. So she worked as a physical science instructor at Howard University for a year and began studying protein structure, until able to secure funding for a seven-year post-doctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society. She moved to the Rockefeller Institute of Medicine in New York City, for the next seven years, where she worked with distinguished scientists and was the only Black scientist there. With Mirsky, she worked on protein synthesis and the metabolism of cellular nuclei, critical and foundational research for developing ideas on the structure of DNA.

She became a biochemist associate for the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia, and at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in1955. There, she taught and continued her research on cancer and nucleic acids while she collaborated with Dr. Quentin Deming at Goldwater Memorial Hospital, on the causes of heart attacks. Her research about arterial walls looked at the effects of aging, hypertension, atherosclerosis (or the build up of fat in arteries), sugar and cholesterol. They showed that hypertension was a precursor to atherosclerosis and were the first to link cholesterol and clogged arteries. In studies of hypertensive rats, she showed the link between high cholesterol and heart attacks. This was the foundation of work to prevent heart attacks. She studied the link between smoking and lung disease and how kidneys affect metabolism. She was a researcher for the American Heart Association from 1958 to 1963, working particularly on stroke research. Columbia made her an assistant professor of biochemistry from 1960-1961. She married Vincent Clark in 1961 (and retained her name professionally).

She and Deming both moved to Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University where she became an assistant professor of biochemistry and medicine (then associate professor from 1971). While there, she started and helped run the Martin Luther King Jr. - Robert F. Kennedy program to help prepare Black students for admission and worked to recruit Black and Puerto Rican students. She also did important work on understanding the uptake of creatine in muscles, including the temperature and ion conditions at which it could be best absorbed. She was a dedicated mentor. She participated in a conference with 30 other minority women in STEM, hosted by the American Association for the Advancement of Science which resulted in in a report called The Double Bind: The Price of Being a Minority Woman in Science (Malcom, Hall, & Brown, 1976).

She was also a cancer scientist with the Heath Research Council of New York from 1962 through 1972. She served on the board of governors of the New York Academy of Science. She was also active in student recruitment and in professional societies and the NAACP and National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women. She was a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

After retirement in 1986, she donated money to Queens College to create scolarships from Black students in physics and chemistry, in honour of her father. She served on the Commision for Science and Technology for New York City for three years, before moving with her husband Vincent Clark to their East Hampton summer home and then to Sarasota, Florida. In 1999, the National Technical Association recognized Daly as one of the top 50 women in STEM. She was devoted to playing the flute, gardening and her dogs; when her cancer made flute playing difficult, she learned the guitar. She died in 2003, at the age of 82, in New York City.

References

Daly, Marie Maynard. Encyclopedia.com, accessed April, 2021.

Galen Scott, Black History Month - Marie Daly, The Researchers Gateway, March 7 2019

Marie M. Daly PhD Memorial Celebration, Einstein University, 2021

Victoria Corless, Pioneers in Science: Marie Daly, Advanced Science News, August 27, 2020

Marie Maynard Daly, Wikipedia, accessed April, 2021.

Jalen Borne, Hidden Figures Beyond: The First Black PhD in Chemistry, Marie Maynard Daly, Charged Magazine, April 3, 2020

Dale DeBlakcsy, Marie Maynard Daly (1921-2003), America's First Black Woman Chemist, Women You Should Know, February 28, 2018

Daniel Tyrell, #BlackCardioInHistory: Dr. Marie Maynard Daly, blackincardio.com, October 20, 2020.

Marie Maynard Daly, Science History Institute, November 9, 2018

Roopati Chaudhary, Marie Maynard Daly, Sci-illustrate, July 14, 2020.