(photograph by Nina Leen)

17. The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing edited by Richard Dawkins. I thoroughly enjoyed this book. There were some excellent selections, interesting themes, authors who were new to me, and I (a professional scientist) learned many things. Some authors are stars or revolutionaries in their fields. Some are scientists with a real gift for communication. A few science writers are represented. Any anthology, as soon as it is published, is open to second guessing about content. I can recommend this book

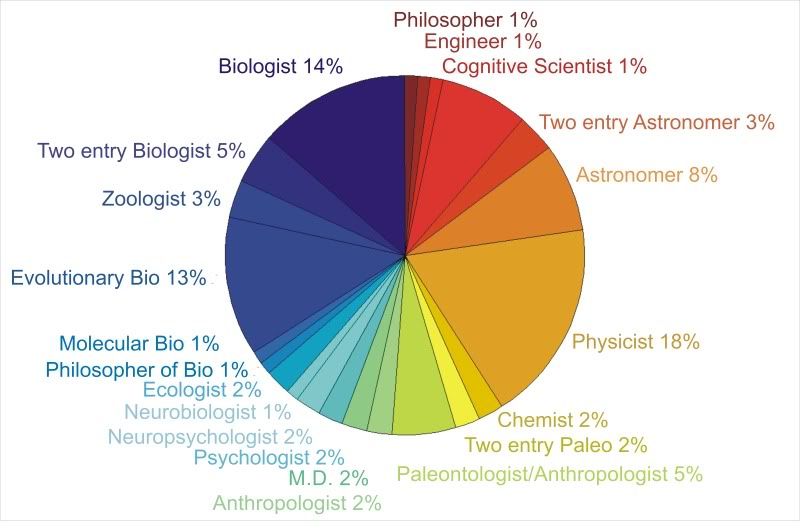

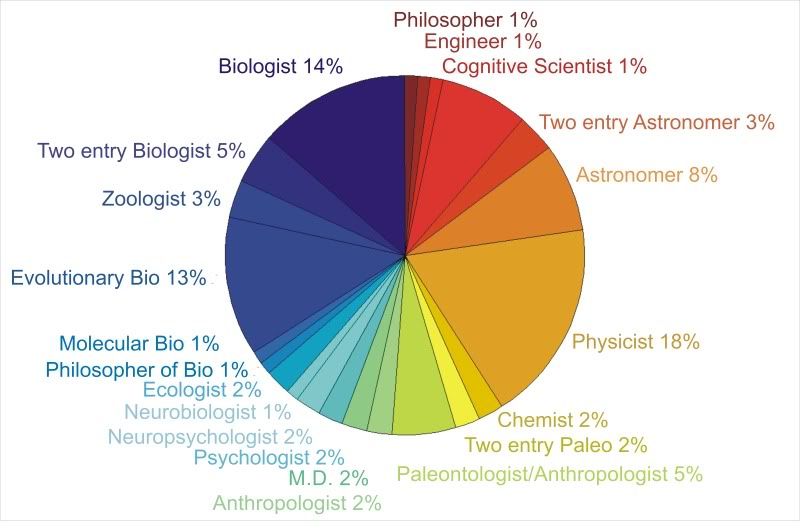

The Oxford Book of Modern Science Evolutionary Biology with Bits of Astrophysics and Some Other Things -Especially Entropy* Writing (note: entropy is over-represented but it is arguably the portion of physics with the most ramifications for, you guessed it, evolutionary biology and genetics) as an excellent repository of some science writing over the last century. The content is

excellent, if biased towards Dawkins' own field of evolutionary biology. Now, when a scientist accuses another scientist of bias, well,

them's fightin' words, but I'm not certain Dawkins would find an accusation of bias in favour of evolutionary biology all that insulting. It's sort of like water to fishes, or the air we breathe; when something is omnipresent sometimes it's difficult to notice. Like a good experimentalist, I thought I would try to be

quantitative, not just

qualitative in my analysis. (

I recognize by presenting statistics in a book review about science writing I'll probably loose my last imaginary reader, but I'm afraid I don't care. Numbers are useful, and our friends, so stick with me!) In order to insure some sort of impartiality, after doing my own count, I switched to identifying author disciplines based on his one-line biographies. So these are disciplines according to Dawkins himself:

Number of entries in the book: 88

Number of Featured Authors: 83 (this does not include hapless co-authors)

You can see that 'soft' or biological sciences in cool colours are well over half the entries, leaving the orange and red 'hard' physical sciences a mere third of the entries. The slight to chemistry seems very odd, but poor Earth and planetary science (geology, geophysics, geochemistry, atmospheric science, oceanography) are not represented at all (though one paleontology entry comes close to geology).

Biological Sciences

Biologists: 12 (4 of whom get two entries)

Zoologists: 3

Evolutionary Biologists: 11

Molecular Biologist: 1

Philosopher of Biology: 1

Ecologists: 2

Neurobiologists: 1

Neuropsychologists: 2

Psychologists: 2

Medical Doctors: 2

Anthropologists:2

Paleontologists & Paleoanthropologists: 5 (2 of whom get two entries)

I confess I would lump a lot of the above into an undifferentiated mass labelled 'biology' or 'soft sciences'.

Earth & Planetary Sciences

Geology: 0 (though in fairness, one of the Paleontologists is pretty close)

Geophysics: 0

Geochemistry: 0 (though one of the chemists give a hint)

Planetary Science: 0 (though some astronomers allude to it)

Atmospheric Physics: 0

Climatology: 0

Oceanography: 0

Physical Sciences

Chemistry: 2

Physics: 16

Astronomy: 7 (3 of whom get two entries and 1 of whom writes about, you guessed it, evolutionary biology)

Frankly, differentiating these last two groups is somewhat arbitrary.

Mathematics: 7

Philosophy: 1 (about, you guessed it, evolutionary biology)

Cognitive science: 1

Engineering: 1

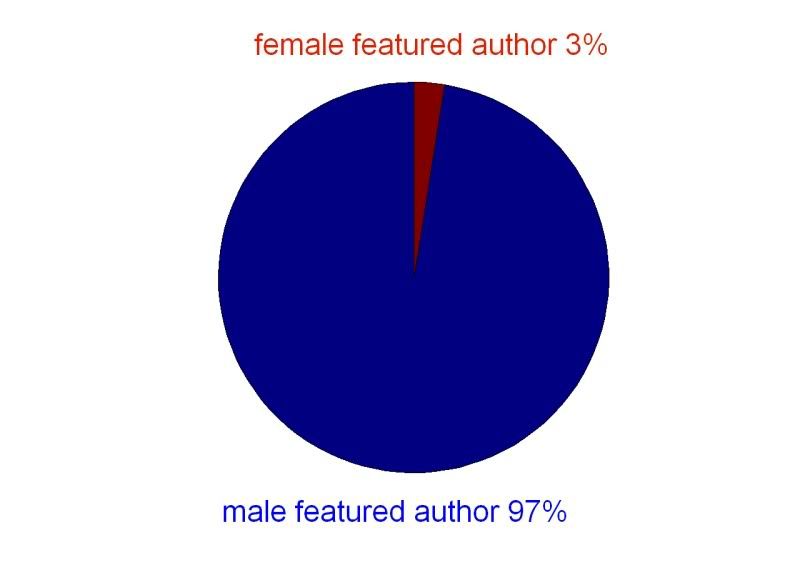

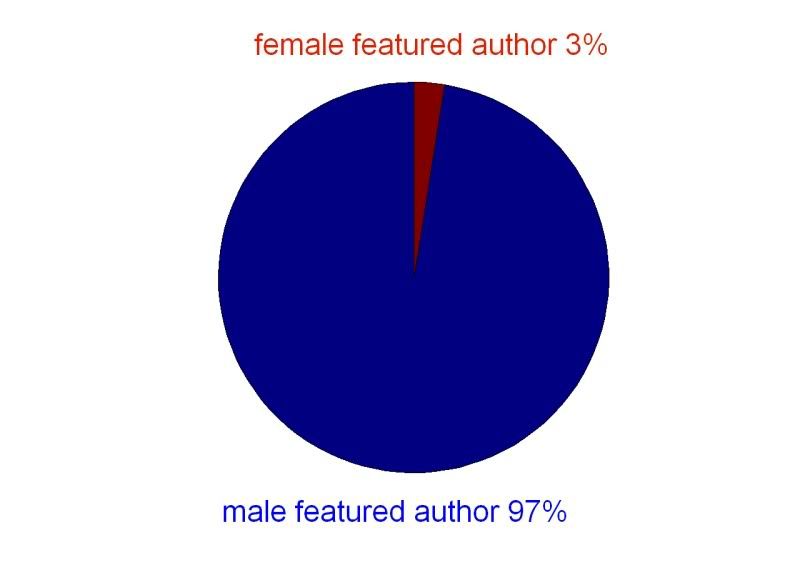

Another bias might be somewhat less obvious, unless plotted.

Male featured authors: 77

Female featured authors: 2

(though one male authour writes about Dorothy Hodgekiss, and Barbara Gamow, not a 'featured' author, gets a half credit for one song, though in the actual book the credit is for the music, not the words)

But, science is male-dominated, you can't imply bias just because an anthology of science writing only has 2.4% entries by female writers.

Can't I? Considering the strong bias towards biological sciences, which are far less male-dominated, in fact, I think allowing women less than one twentieth of their statistical representation in nature, in a discussion of SCIENCE, one of the greatest intellectual achievements of our species, is, in a word

biased. Let me be clear: I use the word not in the colloquial sense to mean close-minded, but in the technical sense to mean that there is a systematic error. The data are not reflective of the candidate population, even when we take into consideration that women represented less than half of all of the sciences included, with decreasing representation the further back in time one looks. The above pie chart might have been somewhat representative in the Middle Ages, but it is strongly skewed for selections since 1900.

I noticed that all the glowing reviews in serious periodicals, and wondered if anyone else objected to this bias. A google search lead to

the book's wikipedia entry which details how well-received the book has been,

but that the book had been critized by many science bloggers for its lack of female authors. If you follow the link you can see some discussion. Dawkins defends himself by claiming "It is not an anthology of 'science writing' ...[rather] It is a collection of writing by good scientists, many of them dead and very distinguished." Strange, as this is not strictly true, since he includes Martin Gardner, a (male) science writer, so he could just as well have included "Olivia Judson and the other admirable science writers" who happen to be female. Further, I do not buy his claim that he was limited by the demographics of scientists from 1900 onward (because the pie chart above still wouldn't match, and would be off by more than a factor of 10, anyway you slice it). Now, I do not think either a) he should include more women merely on principle or b) that there should necessarily be a one-to-one relationship between gender of scientists and authors in the book. However, I do think that even if quality of writing is the sole guide, his list is biased, as there are many excellent female scientists who were or are known for their writing ability. Further, I think that it is harmful to make that group

even more invisible, by implicitly denying their existence. Lastly, readers are missing out on these other voices, and entire fields of science.

For reference I checked a couple of anthologies of science writing which happened to be on my shelf -both managed more than 2 female authors despite beginning at earlier times (mid 19th century) or being limited to physics, the most male-dominated field, respectively.

I will also comment that in an otherwise excellent and fascinating entry on the mathematics of the growth of spirals in nature (in everything from ram's horns to nautilus shells) D'Arcy Thompson repeatedly uses the word 'velocity' in error. He tries to define a spiral as 'If, instead of travelling with

uniform velocity, our point moves along the radius vector with a velocity

increasing as its distance from the pole, then the path described is called an equiangular spiral.' The problem with this, as every high school physics student knows, is that velocity is a vector quantity with a magnitude and a direction. One cannot speak of moving with

uniform velocity while continuously changing your direction. There's a good, simple, old-fashioned, Old English, monosyllabic word that would suit the purpose (where the fancier velocity does not fit). It's called speed. I hate when people use polysyllabic words erroneously rather than simple words correctly. I can only assume our biologist/mathematician/Classicist and our evolutionary biologists/anthologist were ignorant of this fact.

So, now that I've taken an excellent book to task for not being better, I thought I would do the unfair thing and list some people who I feel he left out.

J. Tuzo Wilson - Not only was Tuzo Wilson one of the sources of the major 20th century revolution in earth sciences - plate tectonics (filling that gap in subject matter) - but he was an successful author as well. His seminal (there's a loaded word for someone complaining of gender bias) 1963 paper 'A possible origin of the Hawaiian Islands' is so readable, I would quote it directly even for the lay person.

Derek York Derek was a geochronologist, a leader in his field, whose paper 'Least squares fitting of a straight line with correlated errors' has 1852 citations - its applicability and reach extending far beyond his own field. He also wrote popular science books and a science column for the Globe and Mail. He was, full disclosure, a friend and colleague.

Ted Irving As another revolutionary of plate tectonics - but also a world expert on rhododendrons- I would think his writing about the spread of plants through plate motions would give Dawkins another excuse to talk about evolutionary biology. He is, full disclosure, a friend and was a colleague.

Ursula Franklin I've

already explained why renowned scientist and engineer Ursula Franklin ranks amongst my heroes. She is both a brilliant physical scientists and famous author.

Dava Sobel - astronomer and psychologist by training, first-rate, award-winning science writer by vocation, I think if Martin Gardner met Dawkins' criteria, Sobel does as well.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell - though in a typical move they opted to give the Nobel to her supervisors, for research she did, Jocelyn Bell Burnell is widely recognized as world-class astrophysicist and author and has even edited a volume of poetry.

Melba Philips - developer of the Oppenheimer-Phillips theory of neutron capture renown for her skills at physics education, writer of texts on electromagnetism from the introductory to the graduate level she would have made a great author to add to this collection.

Lisa Randall - well-known particle physicist, cosmologist and author (her allegories recall George Gamow, according to the New Yorker), Randall has also had a popularization of modern particle physics book make the New York Times Bestsellers List.

These are skewed perhaps to physics and geophysics*, but it isn't hard to think of some renown biologists and writers, who happen to be female.

Jane Goodall - renown primate biologist, ecologist and popularizer of science

Olivia Judson - evolutionary biologist and award winning science writer

I can also think of many excellent female science bloggers, but bloggers are probably too hip for Dawkins and OUP.

{Series so far:

books read,

more books read,

books read,

books read continues,

more books read,

I,

II,

III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII,

VIII,

IX,

X,

XI,

XII,

XIII,

XIV,

XV,

XVI,

XVII,

XVIII,

XIX,

XX,

XXI,

XXII,

XXIII XXIV,

XXV,

XXVI,

XXVII,

XXVIII,

XXIX,

XXX,

XXXI,

XXXII,

XXXIII,

XXXIV}

*Also biased towards people I've met, but if I were actually editing an anthology, I could devote some time to acquainting myself with more world-class scientists and authors who I have not met and I would find some chemists, as a matter of principle.

This pillow features my block printed Euoplocephalus dinosaur in mauve on gold silk. The front side is a patchwork with two other contemporary fabrics, one floral the other like marbled paper. The reverse is a patchwork of handwoven Nepalese fabric (screenprinted with leaves by etsy textile artist tanisalexis) and vintage 'gamebird' fabric in earth tones. The pillow is 14.5 inches (37 cm) wide and 11 inches (28 cm) high.

This pillow features my block printed Euoplocephalus dinosaur in mauve on gold silk. The front side is a patchwork with two other contemporary fabrics, one floral the other like marbled paper. The reverse is a patchwork of handwoven Nepalese fabric (screenprinted with leaves by etsy textile artist tanisalexis) and vintage 'gamebird' fabric in earth tones. The pillow is 14.5 inches (37 cm) wide and 11 inches (28 cm) high.

(photograph by Nina Leen)

(photograph by Nina Leen)

I have a weakness for various art, design and fashion blogs. One of the biggest street fashion (cum high fashion) blogs around is The Satorialist. In fact over the course of its existence Sart has gone from amateur to professional, shooting on the streets to shooting at the shows and writing for magazines. They say imitation is the highest form of flattery. The TCA today directed me to The Catorialist! Check it out; they've re-created the The Satorialist look, right down to the

I have a weakness for various art, design and fashion blogs. One of the biggest street fashion (cum high fashion) blogs around is The Satorialist. In fact over the course of its existence Sart has gone from amateur to professional, shooting on the streets to shooting at the shows and writing for magazines. They say imitation is the highest form of flattery. The TCA today directed me to The Catorialist! Check it out; they've re-created the The Satorialist look, right down to the  {image via Daquar} 13. Grimus by Salman Rushdie This is Rushdie's first novel, and it is in fact science fiction (not magical realism). The cover, of course, is replete with "too good to be science fiction" reviews by the usual suspects of serious-periodicals-who-do-not-want-to-be -caught-dead-reading-SF. Mainly it's a fable, but immortality, other dimensions, extra-terrestrial life, and a quest, do play a part, as do anagrams.

{image via Daquar} 13. Grimus by Salman Rushdie This is Rushdie's first novel, and it is in fact science fiction (not magical realism). The cover, of course, is replete with "too good to be science fiction" reviews by the usual suspects of serious-periodicals-who-do-not-want-to-be -caught-dead-reading-SF. Mainly it's a fable, but immortality, other dimensions, extra-terrestrial life, and a quest, do play a part, as do anagrams.