Time for some non-fiction (having read

Seeing I was hoping for something less gut-wrenching).

22. The Eternal Frontier - An Ecological History of North America And Its Peoples by Tim Flannery The Eternal Frontier tells the story of successive waves of invaders of the North American continent. Starting 65 million years ago, (the K-T boundary to an earth scientist) when "a great fiery ball appeared in the sky and came crashing to Earth" with an "unfortunate chip-shot" ending the age of dinosaurs and devastating North America in particular, the book explains the evolution of the continent, the interplay of climate and ecology, in an engaging and fascinating way. It's filled with

relevant colourful details*, such as the role of fossil-hoarding ants in paleontology, or how the nut-stashing squirrels changed the landscape on a large scale and allowed a source of protein far from water bodies for early indigenous peoples, or the story of George McJunkin, self-taught, African-American cowboy-scientist, who in 1908 excavated a bone pit containing entire (extinct) giant bison remains and hunting tools, which completely changed the understanding how long native people had been living on the continent. The book is divided by era (Act 1: 66-59 Million Years Ago - In Which America Is Created And Undone; Act 2: 57-33 Million Years Ago - In Which America Becomes a Tropical Paradise; Act 3: 32 Million to 13,000 Years Ago - In Which America Becomes A Land of Immigrants; Act 4: 11,000 Years Ago - AD 1491 - In Which America is Discovered; Act 5: 1492-2000 - In Which America Conquers The World) which allows him to trace how the changing climate controls the ecology, even on a continental scale. He purposely draws parallels between invasive animal (and even plant) species and later human invaders (First Peoples and later Europeans). He convincingly explains how the shape of North America creates a climatic trumpet, with essentially arctic winters and tropical summers through the bulk of the continent, and how this makes the plant and animal species unique. He's able to make simple arguments about the connection between size of land-mass, diversity, competition and likelihood of success of any invading species. His writing is very engaging: I feel like I now know the drama of the discovery of the Uinta beast, or the character and behaviour of the oreodonts. It left me devastated about the fate of the buffalo, and later wholesale ecological destruction. I was glad to learn that in Canada the Hudson's Bay Company was actively supplying smallpox vaccine to its traders in the 1830s for their native trading partners. At least there was some hint of humanity in the chapter on disease, otherwise filled with tales of evil. The book is well annotated and he is clear about his own biases and explains competing theories. Flannery is an Australian, which gives him a unique view as an outsider on the ecology (and the romance of the frontier) and the effects of invasive species. I can highly recommend this book.

The one disappointment was that he chose to focus on the U.S. - or so he claims. It might seem reasonable, as one must limit a book somewhere, and the scope was ambitious. However, he can't discuss many issues without describing the continent as a whole. No one interested in dinosaurs could avoid mentioning Alberta. He also describes the ancient civilizations of Mexico, and the Inuit of Canada's north. So really, when he says he is limiting the study to the U.S., he means the fifth act only, which then seems quite arbitrary. And it is in Act 5 that his status as an outsider fails him. I don't find his description of North American history, and in particular, unity, since the American Revolution, all that convincing. Though he spends chapters describing settlers, the revolution, and setting-up the North-South cultural differences, he skims through the Civil War in a few paragraphs - where I would have thought the ecological destruction, let alone the death toll, would have demanded much more - claiming it "definitively resolved the tensions that had been evident in British-settled America since its inception". Oh, really? He contrasts the United States of America with Simón Bolívar's unfulfilled South American dreams of unity and even Canada, which he seems to think is falling apart.** Now, in 2001 when the book was first published in Australia, he could be forgiven for writing that Québec's separation seemed imminent. It was, I believe, far from a given (note, it did not happen) - but, it was certainly a possibility. However, when he goes on to lump the threat of Separation with "the statehood and autonomy" achieved by the Inuit in 1999, as examples of "federation in reverse" he simply does not know what he's talking about. He also erroneously uses the word province. The creation of the

territory (the difference between a province and territory is immense, but I'll spare you the gory detail***) of Nunavut was a great triumph for Canada and the Inuit of Nunavut. It is by no stretch of the imagination a sign of the dissolution of this country. Nunavut is very much part of Canada. This was wrong in 2001, and really should be remedied for this new North American release. It's probably flippant to suggest that the American Civil War simply became a cold war, and simmers to this day, but the fact that such a suggestion would be

unoriginal gives the lie to the claim of "

definitively resolved" tensions. Let me contrast two numbers which I think are revealing when considering the nature of confederation on this continent.

Since 1861, the number of deaths which have ensued from the issue of succession versus unityIn Canada: 1

In the U.S.A.: 625,000

I really do no see the U.S. as more united than Canada, and I haven't even broached the issue of voting patterns.

While I agree that "pluralism seems to lie at the heart of the Canadian ideal" I believe he is very mistaken that this indicates disunion. In fact, I think he missed an opportunity to compare and contrast the role of regionalism versus federalism north and south of the border. There are some interesting parallels. In both countries power is balanced between an unruly group of either states or provinces and territories and the federal government who often disagree with each other and amongst themselves. Further, since he takes the idea of a boundless frontier and traces this to mass production and consumerist culture in the U.S., comparing and contrasting this with Canada and Mexico, whose frontiers were likewise vast, would also have been interesting.

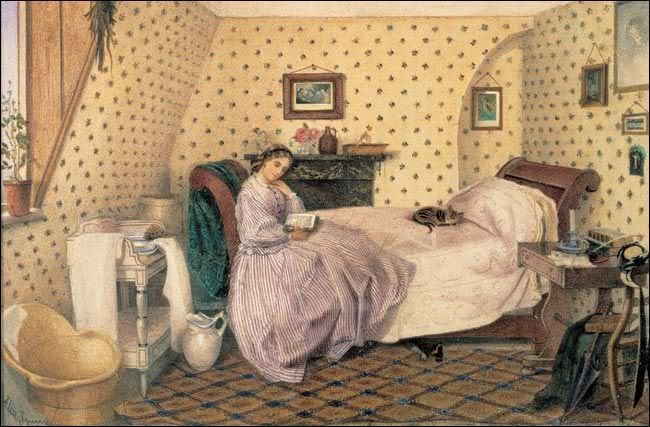

23. The Children's Book by A.S. Byatt This novel is excellent. Read it. It's the story of Victorians, largely Fabian socialists, and their children, the Edwardians who grow up to go to war. In the interim there is much magic. It starts with beautiful Olive Wellwood, lady novelist, who writes successful children's stories, fairytales with just enough darkness, whose research visit to Major Cain and the South Kensington Museum changes lives, when their respective sons Tom and Julian discover Philip, a young, working-class runaway who has been living secretly in the museum. He needs to create things and has come to learn. The novel interweaves the Wellwoods - charming Quaker, black-sheep and Fabian, Humphrey, writer of satires of the socioeconomic situation, Olive, her sister Violet who keeps everything together and their growing family, Tom, the golden boy like Peter Pan, Dorothy, who discovers she has an ambition to be a doctor, pretty Phyllis, headstrong Hedda, and little ones, with the London Wellwoods: banker Basil and German wife Katerina, with daughter Griselda who is interested in stories and son Charles who is moved by his uncle's socialist tirade, with the military-curator Major Cain, whose son Julian is interested in Tom, and beautiful daughter Florence is calm and collected, with local artists, potters and puppermasters and their children. Olive keeps a notebook for each of her children, documenting a never-ending fairytale just for them. Tom's story, a quest to find a stolen shadow underground, draws on Olive's childhood fearing for her father and brother who went down into the coal mines. Dorothy's story is of shape-shifters and a hedgehog skin. These stories, Olive's own published stories and the lives of the parents and children are seamlessly worked together. Byatt often includes fairytales in her novels and in this novel in particular, I find, that it's magic. It is integral to the tapestry in which the novel itself progresses. The story is told against a backdrop of changing social mores, increases fluidity of the class structure, socialism, anarchism, Marxism, a growing awareness of women's rights and the battle for the vote, acknowledgment that children are children and not miniature adults, but children, who have a need to play and develop, growing acknowledgment of human sexuality (without proper birth control, and with hypocritical consequences and responsibilities for mothers, of course), irresponsible speculative financial markets, fading imperialistic ambitions and the build up to world war. Further, the literature and writers of the times are part of the fabric of the book, from the tragedy of Oscar Wilde, exiled in Paris, H.G. Wells' fiction and his role in the Fabian society, through Lewis Caroll's Alice, and J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan, or both the furniture, art and writing of William Morris and the arts and crafts movement and art deco. It's telling that Aunt Violet likes to tell the children about the cuckoo, and how hard it is to

know who one's parents really are. Eventually the children, of course, loose their innocence, and learn some things they might not have wanted to know. They create their own lives, as artists, scholars, suffragettes, lovers, anarchists, potters, puppeteers, doctors, martyrs, heroes, soldiers, husbands, wives and parents, or not, in a world forever changed by a larger loss of innocence. It's quite beautiful, dark and real.

24. The Periodic Table by Primo Levi I thought it was high time I read this book. The cover is filled with surprised reviews by people who wouldn't have thought that the elements would make such apt muses, but I guess they must know little chemistry. To chemist, and memoirist, Primo Levi, the elements themselves are filled with connotations, metaphoric, historic and inspiration for pure storytelling. He begins with Argon, a Noble gas, as a means to discuss his heritage, ancestors and their unique blend of Pietmontese and Hebrew languages. He proceeds to work through other elements (but not the periodic table itself in any systematic way), and tells sorties about his experiences as a boy interested in science, as a chemistry student, as a rock-climber, as a chemist, mainly before and after, but sometimes during (in a concentration camp) WWII. A few of his early stories are blended in to this mix. He is a great observer, both as a creative, experimental chemist of course, but also of people and the series of sketches of the people in in life are very evocative. Mysteries about seeking the elements themselves and revelations about people appear in equal measure. I enjoyed both the romance of the chemistry itself, and the memoir of his life.

*I'm looking at you Simon

I never saw an irrelevant tangent I didn't like especially if it allows me to show off my research or compliment my alma mater, Oxford, of course Winchester.

**This is a good way to irk federalist Canadians.

***Canadians consider any discussion of Constitutional Law as

cruel and unusual punishment to be avoided at all costs.

{Series so far:

books read,

more books read,

books read,

books read continues,

more books read,

I,

II,

III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII,

VIII,

IX,

X,

XI,

XII,

XIII,

XIV,

XV,

XVI,

XVII,

XVIII,

XIX,

XX,

XXI,

XXII,

XXIII XXIV,

XXV,

XXVI,

XXVII,

XXVIII,

XXIX,

XXX,

XXXI,

XXXII,

XXXIII,

XXXIV,

XXXV,

XXXVI,

XXXVII}

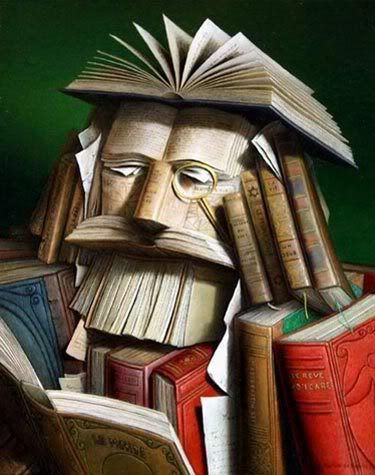

(image by Andre Martins de Barros)

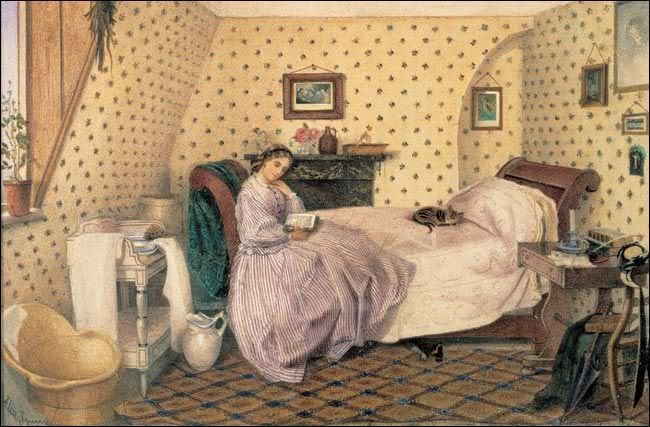

(image by Andre Martins de Barros)

Time for some non-fiction (having read Seeing I was hoping for something less gut-wrenching).

Time for some non-fiction (having read Seeing I was hoping for something less gut-wrenching).