Today is the fourth annual international day of blogging to celebrate the achievements of women in technology, science and math, Ada Lovelace Day 2012 (ALD12). I'm sure you'll all recall, Ada, brilliant proto-software engineer, daughter of absentee father, the mad, bad, and dangerous to know, Lord Byron, she was able to describe and conceptualize software for Charles Babbage's computing engine, before the concepts of software, hardware, or even Babbage's own machine existed! She foresaw that computers would be useful for more than mere number-crunching. For this she is rightly recognized as visionary - at least by those of us who know who she was. She figured out how to compute Bernouilli numbers with a Babbage analytical engine. Tragically, she died at only 36. Today, in Ada's name, people around the world are blogging about women in science and technology, whose accomplishments have all too often gone unrecognized or unacknowledged.

Today is the fourth annual international day of blogging to celebrate the achievements of women in technology, science and math, Ada Lovelace Day 2012 (ALD12). I'm sure you'll all recall, Ada, brilliant proto-software engineer, daughter of absentee father, the mad, bad, and dangerous to know, Lord Byron, she was able to describe and conceptualize software for Charles Babbage's computing engine, before the concepts of software, hardware, or even Babbage's own machine existed! She foresaw that computers would be useful for more than mere number-crunching. For this she is rightly recognized as visionary - at least by those of us who know who she was. She figured out how to compute Bernouilli numbers with a Babbage analytical engine. Tragically, she died at only 36. Today, in Ada's name, people around the world are blogging about women in science and technology, whose accomplishments have all too often gone unrecognized or unacknowledged.

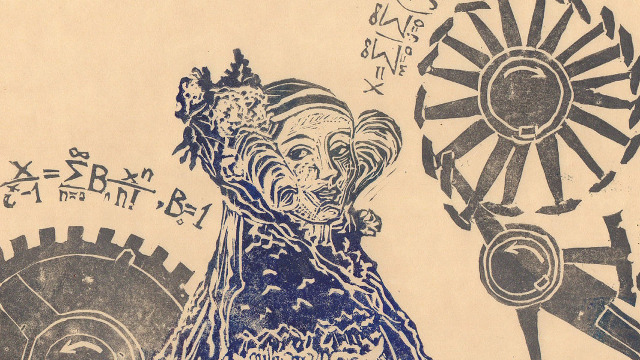

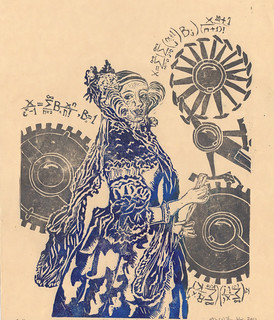

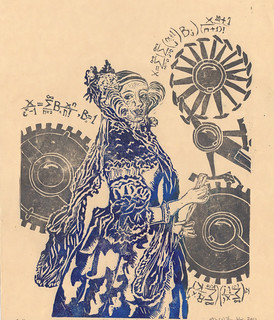

I made a new edition of my 'Ada, Countess Lovelace' print for the occassion. The print is in blue, indigo and dark silver water-based block printing ink on cream coloured Japanese kozo paper 12.5 inches x 10.5 inches (31.8 cm x 26.7 cm). There are 4 prints in this second edition. The first edition was printed on plum coloured paper.

This year, I would like to tell you about Lise Meitner. I made her portrait along with her explanation of nuclear fission. She was the first person to provide a theoretical explanation for nuclear fission and was an integral member of the experimental team as well, though her gender and her heritage interfered with her being properly acknowledged in late 30s Germany.

Meitner is shown in dark silver ink with a neutron flying from her brow towards a uranium nucleus, and the ensuing chain reaction is shown in red. The print is in an edition of 6 printed on white Japanese kozo (or mulberry) paper, 12.3 inches by 12.5 inches (31.2 cm by 31.8 cm).

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner (7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was a world-class physicist who collaborated with chemists

Otto Hahn and

Fritz Straßmann1 in the 1930s in Berlin. The team was investigating whether there were any stable elements beyond uranium, on the periodic table. They discovered that by bombarding the nucleus of uranium-235 with neutrons that they actually triggered it to fission, or break, into two nuclei of roughly half the size and some free neutrons! Hahn's chemistry allowed the startling discovery and identification of barium, but no explanation of the mechanism involved; Meitner's physics provided the explaination of how fission could be possible and its implications. Otto Hahn was awarded the 1945 Nobel prize for chemistry. Though Meitner won many accolades, the Nobel committee neglected her contribution, in one of the most blattant and eggregious instances of their overlooking women's scientific acheivements.

Hahn and Meitner's research was disrupted by WWII. Meitner was of Jewish heritage. Her Austrian citizenship provided her some protection prior to its annexation, when she had to make a daring escape via the Netherlands to a new home in Sweden, in 1938. Despite their seperation, Meitner and Hahn continued to work together, planning the experiments which lead to the discovery of fission at a meeting in Copehagen. Hahn and Straßmann performed the experiments and Hahn realized that the presence of barium could only make sense if the nuclei had split, but he needed Meitner's help to understand how this could be. Meitner was able to apply the latest physics, the

liquid-drop model of the nucleus (as shown in my print), to explain how the absorption of an extra neutron could produce an unstable nucleus which split into two large pieces, the daughter nuclei, and more free neutrons. Most importantly she saw that the combined mass of the neutron and uranium-235 was larger than the products and that the 'missing mass' would all be transformed into vast amounts energy according to Einstein's famous equation E = mc². She also saw how the newly produced high-energy neutrons would in turn strike other uranium nuclei, leading to a chain reaction. She worked with her nephew, physicist

Otto Frisch to develop this theory. In Germany in 1939, Hahn could not publish jointly with Meitner. Hahn and Straßmann submitted the team's results (that bombarding uranium with neutrons produced barium) for publication in 1938. Meitner and Frisch interpreted these results correctly as nuclear fission in Nature in 1939.

The physics community recognized that the huge energies produced by these fission chain reactions could be used to produce a bomb, and further, that expertise existed in Nazi Germany. Physicists on the Allied side, lead by

Leó Szilárd,

Edward Teller, and

Eugene Wigner immediately worked to persuade Albert Einstein

2 (whose fame would receive attention) to bring this danger to the attention of F.D. Roosevelt, which ultimately lead to the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb. Meitner herself refused to be involved in weapons research or the Los Alamos project and declared, "I will have nothing to do with a bomb!"

3 She never returned to Germany or her Austrian homeland, even after the war, making a life in Sweden and retiring to England. Her nephew Otto Frisch composed the inscription on her headstone. It reads "Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity."

Apart from her role in discovering and explaining nucleur fission, Meitner had many great acheivements. She was the only second woman to be granted a doctoral degree in physics by the University of Vienna, where she studied with the great

Ludwig Boltzmann.

4 She moved to Berlin and worked for

Max Planck5 (who had previously refused to admit women) before beginning her 30-year long collaboration with Otto Hahn. Together with Hahn in 1917, she discovered the first long-lived isotope of the element protactinium, for which she was awarded the Leibniz Medal by the Berlin Academy of Sciences. That year, Meitner was given her own physics section at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry. (It's worth noting that she and Hahn were relegated to a basement lab because women had not been allowed in the building, and that she had to go to another building to find a woman's washroom). In 1926, Meitner became the first woman in Germany to assume a post of full professor in physics, at the University of Berlin. She was praised by Albert Einstein as the "German Marie Curie". She visited the US in 1946, where she was hailed as a heroine and received the honour of the "Woman of the Year" by the National Press Club, many honorary doctorates and lectured at Princeton, Harvard and other US universities. She received the Max Planck Medal of the German Physics Society in 1949. Meitner was nominated to receive the Nobel prize three times. In 1966 Hahn, Fritz Straßmann and Meitner together were awarded the Enrico Fermi Award. In 1997, the element 109 was named meitnerium in her honour. Today the Hahn-Meitner Institut in Berlin, craters on the Moon and on Venus, and a main-belt asteroid are all named in her honour.

(This post was made with information from

Lise Meitner's wikipedia entry and Sime's biography.

Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics by Ruth Sime is one of the best biographies I have ever read. I recommend it highly to anyone interested.)

1 Straßmann, incidentally, was hired by Hahn and Meitner at a time he could not be hired elsewhere in Germany. He had resigned from the Society of German Chemists when it became part of a Nazi-controlled public corporation and was blacklisted. Hahn and Meitner were able to make a position for him at half pay. He and his wife hid a Jewish friend in their apartment, during the war, at great personal risk to their family.

2 The irony is that Einstein had been a dedicated pacificist throughout his life. At the onset of WWI, Meitner had not been able to see his point of view. Her experience as a nurse handling X-ray equipment during WWI changed her attitudes about war. (Contrast this with Hahn's WWI work developing chemical warfare under Fritz Haber, and we return once again to the question of the scientist's ethical obligations. Haber, incidentally, died in exile in 1938, because of his own Jewish heritage). Einstein saw the Nazi threat as such that it warranted pursuing an Allied fission bomb to avoid being devastated by a Germany weapon. He, of course, later denounced using the bomb as a weapon and campaigned against further development of nuclear weapons.

3 Ruth Lewin Sime, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics (University of California Press, 1996), 305

4 Sime's biography made me a huge fan of Ludwig Boltzmann. He was a talented and kind man. He fought for his wife's right to study mathematics in the 1870s. He was a great teacher and dedicated mentor to his students, including Meitner. Tragically, he suffered from bipolar disorder and took his own life.

5 Planck's own wartime experience is quite the story. He worked hard to shield his employees at the KWG from open conflict with the Nazi regime, though he thought Hahn's suggestion of a public proclamation by scientists, against the treatment of their Jewish colleagues, would be futile. He helped secretly employ Jewish scientists and the blacklisted Straßmann. He held a memorial meeting for Fritz Haber in 1935. He was accused of being "a white jew" by Johannes Stark (Nobel Laureate and Nazi) for continuing to teach Einstein's theories. His own son Erwin, was implicated in the attempt made on Hitler's life in the July 20 plot, and was killed by the Gestapo. Though this and other personal tragedies made the end of his life very difficult, he survived to see a the Nazis defeated and lived to 1947.