|

| Charles Lyell, by Alexander Craig in 1840 when Lyell was 43 years old. |

Recently I got a suggestion from geology for my ‘imaginary friends of science’ series (hat tip to Greg Priest). This imaginary friend is a bit obscure but fits perfectly. Early geologist Charles Lyell (1797-1875), in his famous ‘Principles of Geology’ wrote that to avoid some sources of prejudice in understanding geology would require an Amphibious Being, who could, say, compare processes happening today on land and those happening today below water with what we see in the geological record. Likewise the Amphibious Being would be better able to identify fossils, being familiar with life on land and in the sea. He wrote,

It should, therefore, be remembered, that the task imposed on those who study the earth's history requires no ordinary share of discretion; for we are precluded from collating the corresponding parts of the system of things as it exists now, and as it existed at former periods. If we were inhabitants of another element—if the great ocean were our domain, instead of the narrow limits of the land, our difficulties would be considerably lessened; while, on the other hand, there can be little doubt, although the reader may, perhaps, smile at the bare suggestion of such an idea, that an amphibious being, who should possess our faculties, would still more easily arrive at sound theoretical opinions in geology, since he might behold, on the one hand, the decomposition of rocks in the atmosphere, or the transportation of matter by running water; and, on the other, examine the deposition of sediment in the sea, and the imbedding of animal and vegetable remains in new strata. He might ascertain, by direct observation, the action of a mountain torrent, as well as of a marine current; might compare the products of volcanoes poured out upon the land with those ejected beneath the waters; and might mark, on the one hand, the growth of the forest, and, on the other, that of the coral reef.

-Charles Lyell, 'Principles of Geology' 9th ed. 1853

|

| James Hutton during fieldwork, by John Kay |

He actually goes on to further propose other biases could be avoided only if one could live also in the subterranean world, and hence, a further imaginary friend, "some "dusky melancholy sprite," like Umbriel, who could "flit on sooty pinions to the central earth," but who was never permitted to "sully the fair face of light," and emerge into the regions of water and of air" but such a sprite would have biases due to his lack of access to life on land or in the sea! Here I'm just going to consider the Amphibious Being.

|

| The Geologist - Carl Spitzweg, circa 1860 |

|

| Rise of Mr. de Saussure to the summit of Mont Blanc, aquarellée engraving of Christian of Mechel (1737- 1817). |

|

| Professor Owen, by Frederick Watty in Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day (1873) |

My question is, what would such an Amphibious Being look like? I made my Demons (Maxwell's, Laplace's and Descartes') ressemble those who introduced them with some additional features like horns. There are a lot of images of Lyell at various ages. He is always wearing a suit, with a magnifying glass or monocle on a chain around his neck. There are sadly no images of him in the field. I tried to find some images of early geologists or Victorian geologists in particular. It's easy to find depictions of James Hutton (1726-1797) in the field, but not Lyell. Even searching for Victorian geologists in general proved hard. The vast majority of paintings or later photographs show middle class men in suits at home. There are some hilariously heroic posed images of geologists with hammers looking like Classical heroes. I was pleased so see images of Mary Anning, Alice Wilson and other trail-blazing women in geology come up in my search. The Rise of Mr. de Saussure to the summit of Mont Blanc, an aquarellée engraving of Christian of Mechel (1737- 1817), shows that geologists of Lyell's time did in fact where suits in the field, and some of the simple tools they employed: walking sticks, rakes, shovels and packs of supplies. There are also a number of photographs of somewhat scruffier Gold Rush geologists in California or the Yukon. Along with simple tools, geological hammers, magnifying glasses, and collecting bags are common. I wondered also about Victorian caricatures? I have seen cariactures of various well-known historical scientists (even if scientists seem to rarely be the sort of recognizable public figure to appear in cartoons today). So I looked up cariatures of Charles Lyell and was not disappointed.

|

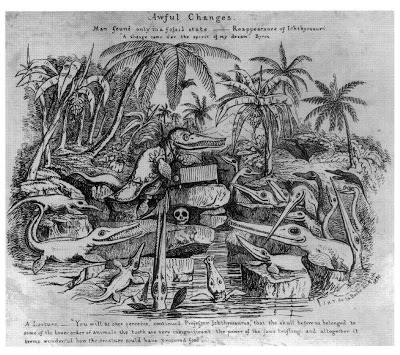

| 'Awful Changes' - Caricature of Charles Lyell as Prof. Ichthyosaurus, by geologist Henry De la Beche (1796 -1855) on

the pages of Francis Trevelyan Buckland (Son of William B.). "Curiosities of Natural History". |

|

| Ichthyosaurus caricature published in 1885 in the

Punch magazine. The discovery of ichthyosaurus fossils lead to interest in reportings of sea monsters, including for Charles Lyell who wanted to support his idea that animals did not become extict, only rare. He wisely did not include this idea in his geology textbook. (via History of Geology) |

The Professor Ichthyosaurus, though an actual, contemporary and amusing cariature of Lyell as a being, which in the cartoon at least, appears amphibious, isn't quite what I want. The itchyosaurus was a marine reptile, not an amphibian. The lecture setting does not suggest fieldwork, nor any greater insight into geology because of its amphibious nature.

Henry de la Beche, incidentally, famously painted the first paleoart scene, Duria Antiquior, based largely on his friend Mary Anning's findings and he sold lithographic prints of his painting to raise funds to help support her. I thought of him as more modern and kind, in his loyalty and friendship with Mary Anning, a paleontologist who was largely excluded due to her sex, class and religion. But in researching this my opinion of him fell. While he understood slavery was an abomination, since his own income depended on an enheirtance of a sugar plantation in Jamaica worked by enslaved people, he (guiltily) opposed abolition in favour of in favour of gradual change. 'This is wrong but let's not be too hasty' is not an ethical stance.

|

| Duria Antiquior – A more Ancient Dorset is a watercolour painted in 1830 by the geologist Henry De la Beche |

And what about the all-important "amphibious" part of my Amphibious Being? My first thought was salmanders. I love the look of gill-stalks and perhaps they suggested Lyell's substantial sideburns. I find the axolotl looks quite anthropomorphic as it is (as reflected in Julio Cortazar's short story, Axolotl). The axolotl is of course limited in range to Mexico, and though other salamanders go through a larval stage with gill-stalks, this didn't feel quite right or in any way an allusion to Lyell. My next thought was to look at Victorian cariatures of anthropomorphic frogs, which (for reasons I don't entirely understand) was very much a thing. Frog men cariatures and Christmas cards and other illustrations, sometimes to satirize society are pretty common, so I thought that was just the thing.

I am now sketching a Victorian frog-man geologist for my next Imaginary Friends of Science print!