Wednesday, March 26, 2014

♥♥♥

Another ♥s milestone on things from secret minouette places yesterday - undoubtedly thanks to the Etsy blog article! The shop now has more than 2300 fans! It's gratifying,

encouraging feedback from the invisible people out there on the internet

who actually find and appreciate my work. So, I'd like to take a moment

to thank each and every one, as well as the 866 Etsy followers, 909 twitter followers, 1541 pinterest followers, 619 fans of the things from secret minouette places fanpage, and last but not least, anyone who follows this blog!

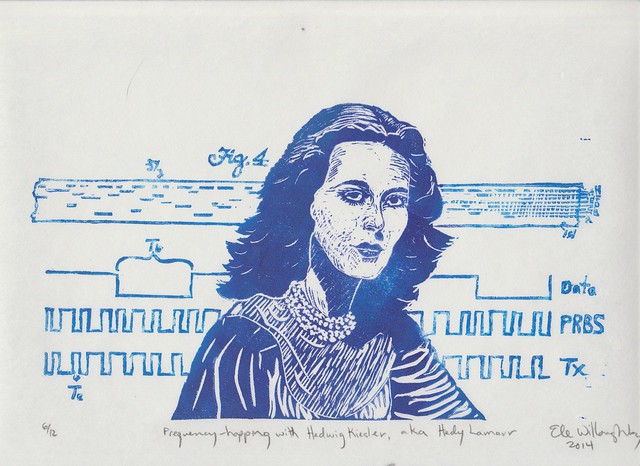

Hedy Lamarr, inventor of Frequency Hopping

|

| Frequency-hopping with Hedwig Keisler, aka Heday Lamarr, linocut by minouette |

This linocut portrait is of inventor and actress Hedy Lamarr (9 November 1914 – 19 January 2000), best known as a star of Hollywood's Golden Age. The linocut is printed in indigo and blue on Japanese kozo paper 9.25" by 12.5" (23.5 cm by 32 cm), inked à la poupée in an edition of 12.

Born Hedwig Keisler in 1914 in Vienna, Hedy became famous after her risqué and notorious starring role in Gustav Machatý's 1933 film Ecstasy. Friedrich Mandl, her first of six husbands (to whom she was married at the time), objected to what he felt was exploitation of his wife, including shots of her nude and simulating an orgasm. He tried unsuccessfully to buy up all copies of the film. Hedy objected to her husband, the munitions manufacturer, dealing with fascists including Mussolini and Hilter, despite the fact that she and her husband were both of Jewish heritage. Hedy had learned that the secret of her beauty was to, in her words "stand there and look stupid” though she was in fact highly intelligent, a mathematics prodigy, and an astute innovator. So while Axis leaders and arms dealers attended lavish parties at their castle home, Hedy gained a great deal of sensitive military intelligence, including intimate knowledge of the problems associate with radio-control of torpedoes. She decided to leave her controlling husband. She made her escape by disguising herself as her own maid (by drugging her and stealing her clothes), just in time to avoid the annexation of Austria. She took this intelligence with her to Paris, and on to London. In London she met Louis B. Mayer, who renamed her 'Hedy Lamarr' and hired her to work for MGM. She went on to make dozens of Hollywood films opposite all the big stars of the Golden Age, and was known as one of the most beautiful women in the world.

In 1940, spurned by the tragic sinking of a boatload of refugees, by a German U-boat torpedo, Hedy put her mind to the problem of national defense. She knew that torpedoes were guided by radio signals, of a single frequency, which were vulnerable to interference or "jamming". She had the idea that if multiple frequencies were employed, like a radio station which varied its channel unpredictably, it would not be possible for the enemy to find and interfere with the signal. This way the signal could be encoded across a broad spectrum. The difficulty would be in synchronizing the transmitter and the receiver, so they would be set at the appropriate frequency at all times. She met her neighbour, the avant-guard musician and composer George Antheil at a party. He had been working on automated control of musical instruments, including his music for Ballet Mécanique which involved synchronizing his melodies across twelve player pianos (or pianolas)! Is that not an excellent example of the wonderous region where art and science intersect? This was the answer. Together they developed Hedy's frequency-hopping idea, encorporating George's technology for synchronizing pianolas, and on the 11th of August, 1942, US Patent Number 2,292,387 for the "Secret Communications System" was granted to Antheil and to “Hedy Kiesler Markey”, which was her married name at the time. This early version of frequency hopping used a piano-roll to change among 88 frequencies (like the keys on a piano). Though the US navy did not adopt the method until 1962 (during their blockade of Cuba), and there other patents and inventors whose work contributed the modern methods, today, we recognize Hedy Lamarr as an important pioneer of wireless technology! Lamarr's and Antheil's frequency-hopping idea serves as a basis for modern spread-spectrum communication technology, such as Bluetooth, COFDM (used in Wi-Fi network connections), CDMA (used in some cordless and wireless telephones) and 4G LTE communications. You are probably using a device right now which relies on these ideas.

In the print, I show a portrait of Hedy in 1941, along with Fig.4 from Lamarr and Antheil's patent, which relates to the use of the piano roll. Below this, I show a diagram of how the modern the frequency-hopping code division multiple access (FH-CDMA) scheme works. The wide square wave labelled 'Data' is a signal to be encoded, with pulse width Tb. 'PRBS' means pseudo random binary sequence. It's the way the changes in frequency are introduced and plays the role of the piano roll today. It runs at a much higher rate than the data to be transmitted, with pulse width Tc. Data for transmission is combined via bitwise XOR (exclusive OR) with the faster code. This means that that if the two waveforms, the data and the PRBS are unequal, the transmitted signal (labelled Tx) will be high. Otherwise the transmitted signal will be low. The transmitted signal is spread across a spectrum of frequencies by a factor determined by the ratio of the two pulse widths; the bandwidth is increased by a factor of Tb/Tc. Since the PRBS, known as the "pseudo-noise" (PN) code can be can be reproduced in a deterministic manner by the intended receiver (which is equivalent to reproducing the imaginary piano roll), it can decode the signal. This spread spectrum encoding is at the heart of all our contemporary telecommunications and is only possible using the kind of frequency hopping that Hedwig Kiesler, also known as Hedy Lamarr, invented.

Born Hedwig Keisler in 1914 in Vienna, Hedy became famous after her risqué and notorious starring role in Gustav Machatý's 1933 film Ecstasy. Friedrich Mandl, her first of six husbands (to whom she was married at the time), objected to what he felt was exploitation of his wife, including shots of her nude and simulating an orgasm. He tried unsuccessfully to buy up all copies of the film. Hedy objected to her husband, the munitions manufacturer, dealing with fascists including Mussolini and Hilter, despite the fact that she and her husband were both of Jewish heritage. Hedy had learned that the secret of her beauty was to, in her words "stand there and look stupid” though she was in fact highly intelligent, a mathematics prodigy, and an astute innovator. So while Axis leaders and arms dealers attended lavish parties at their castle home, Hedy gained a great deal of sensitive military intelligence, including intimate knowledge of the problems associate with radio-control of torpedoes. She decided to leave her controlling husband. She made her escape by disguising herself as her own maid (by drugging her and stealing her clothes), just in time to avoid the annexation of Austria. She took this intelligence with her to Paris, and on to London. In London she met Louis B. Mayer, who renamed her 'Hedy Lamarr' and hired her to work for MGM. She went on to make dozens of Hollywood films opposite all the big stars of the Golden Age, and was known as one of the most beautiful women in the world.

In 1940, spurned by the tragic sinking of a boatload of refugees, by a German U-boat torpedo, Hedy put her mind to the problem of national defense. She knew that torpedoes were guided by radio signals, of a single frequency, which were vulnerable to interference or "jamming". She had the idea that if multiple frequencies were employed, like a radio station which varied its channel unpredictably, it would not be possible for the enemy to find and interfere with the signal. This way the signal could be encoded across a broad spectrum. The difficulty would be in synchronizing the transmitter and the receiver, so they would be set at the appropriate frequency at all times. She met her neighbour, the avant-guard musician and composer George Antheil at a party. He had been working on automated control of musical instruments, including his music for Ballet Mécanique which involved synchronizing his melodies across twelve player pianos (or pianolas)! Is that not an excellent example of the wonderous region where art and science intersect? This was the answer. Together they developed Hedy's frequency-hopping idea, encorporating George's technology for synchronizing pianolas, and on the 11th of August, 1942, US Patent Number 2,292,387 for the "Secret Communications System" was granted to Antheil and to “Hedy Kiesler Markey”, which was her married name at the time. This early version of frequency hopping used a piano-roll to change among 88 frequencies (like the keys on a piano). Though the US navy did not adopt the method until 1962 (during their blockade of Cuba), and there other patents and inventors whose work contributed the modern methods, today, we recognize Hedy Lamarr as an important pioneer of wireless technology! Lamarr's and Antheil's frequency-hopping idea serves as a basis for modern spread-spectrum communication technology, such as Bluetooth, COFDM (used in Wi-Fi network connections), CDMA (used in some cordless and wireless telephones) and 4G LTE communications. You are probably using a device right now which relies on these ideas.

In the print, I show a portrait of Hedy in 1941, along with Fig.4 from Lamarr and Antheil's patent, which relates to the use of the piano roll. Below this, I show a diagram of how the modern the frequency-hopping code division multiple access (FH-CDMA) scheme works. The wide square wave labelled 'Data' is a signal to be encoded, with pulse width Tb. 'PRBS' means pseudo random binary sequence. It's the way the changes in frequency are introduced and plays the role of the piano roll today. It runs at a much higher rate than the data to be transmitted, with pulse width Tc. Data for transmission is combined via bitwise XOR (exclusive OR) with the faster code. This means that that if the two waveforms, the data and the PRBS are unequal, the transmitted signal (labelled Tx) will be high. Otherwise the transmitted signal will be low. The transmitted signal is spread across a spectrum of frequencies by a factor determined by the ratio of the two pulse widths; the bandwidth is increased by a factor of Tb/Tc. Since the PRBS, known as the "pseudo-noise" (PN) code can be can be reproduced in a deterministic manner by the intended receiver (which is equivalent to reproducing the imaginary piano roll), it can decode the signal. This spread spectrum encoding is at the heart of all our contemporary telecommunications and is only possible using the kind of frequency hopping that Hedwig Kiesler, also known as Hedy Lamarr, invented.

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

Inspired by Science on the Etsy Blog

Inspired by Science on The Etsy Blog

The Etsy blog just posted Karen Brown's article featuring 5 Etsy artists who are inspired by science, including me!

|

| Lise Meitner and Nuclear Fission Linocut History of Physics by minouette |

“I think the idea that art and science are separate is unfounded,” says print maker Ele Willoughby of minouette. “It takes creativity to be a good scientist and experimentation to be a good artist.” In her Etsy shop, Ele explores art and science through a series of portraits of scientists inspired by the bi-monthly challenges of the Mad Scientists of Etsy team. “I love hearing from parents who want to inspire young children with portraits of scientific heroes or heroines,” she says.

There are some fabulous artists in that inspiring intersection of art and science, and several of my prints included.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

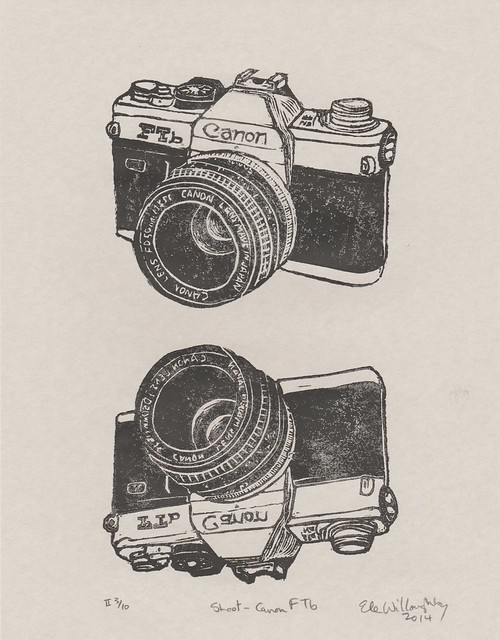

Shoot, the Canon version

The other recent custom order was inspired by my 'Shoot'

linocut showing a vintage Leica M6 and its reflection, which I made for

RJH. By a strange coincidence, one of my brother's buddies found it

online while seeking actual vintage cameras, without realizing I was the

OB's sister. He asked me to create a similar linocut, featuring a

camera he does own (unlike the Leica M6, which would bust most budgets) -

the 1973 Canon FTb. So, I made 'Shoot - Canon FTb':

Wednesday, March 19, 2014

Florence Nightingale

|

| Florence Nightingale, linocut inked à la poupée with chine collé in an edition of four, on Japanese kozo paper 9.25" by 12.5" (23.5 cm by 32 cm), by Ele Willoughby (aka minouette) |

I confess that Florence Nightingale wasn't on my shortlist of women in science I wished to portray. I felt a little like she was an old-fashioned heroine, from a time where if a woman wasn't going to be defined strictly as a person who served and cared for her family, it was okay if (and only if) she cared for other people. This bias was somewhat reinforced by my own family history: my mother is a nurse, her mother was a nurse, whereas I am a physicist. I know my grandmother wanted to be a pharmacist, and my mother felt her career options were school teacher or nurse. Plus, I take after my father's side of the family and have been known to have a vasovagal response to the mere description of medical procedures; I have a high pain threshold, but am squeemish, and faint like the rest of them. I tend to find watching or thinking about others induring something is worse than say, being injured myself.* All of which means I partially define myself by not being a nurse. However, I was (luckily) commissioned to make a portrait of Florence Nightingale. The more I read, the more interesting she became to me.

Nightingale earned the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp" during the Crimean War, from a phrase used by The Times, describing her as a “ministering angel” making her solitary rounds of the hospital at night with “a little lamp in her hand”. The image was immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1857 poem Santa Filomena in the stanza:

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

So, I’ve shown Nightingale with her little lamp, based on contemporary photos and illustrations. But inventing modern nursing wasn't her only accomplishment. Taking up a profession, travelling to a war zone, nursing the wounded, taking on hospital administration and the training of a professional class of nurses weren't the only things she did which were so unusual for a woman of her time to do. It turns out that her father fostered her gift for mathematics, and she made significant contributions to statistics and data visualization too.

Behind Nightingale is her own ‘Diagram of Causes of Mortality in the Army in the East’ plotted as a polar area diagram – though not her own statistical and data visualization innovation, sometimes called a Nightingale Rose Diagram. It illustrates the causes of death in the military hospital she managed during the Crimean War. April 1855 to March 1856 is shown on the left and April 1854 to March 1855 to the right. When she researched the causes of mortality, looking back at the data, she saw clearly that the lack of hygiene was a far greater risk to soldiers’ lives than being wounded. The sections represent one month of data {J,F,M,A,M, J,J,A,S,O,N,D} for each month of the year. The green “wedges measured from the centre of the circle represent area for area the deaths from Preventible or Mitigable Zymotic diseases, the [yellow] wedges measured from the centre the deaths from wounds, & the [orange] wedges measured from the centre the deaths from all other causes. The […] line across the [yellow] triangle in Nov. 1854 marks the boundary of the deaths from all other causes during the month. In October 1854, & April 1855, the [orange] area coincides with the [yellow], in January & February 1856, the [green] coincides with the [orange]. The entire areas may be compared by following the [green], the [yellow], & the […] lines enclosing them.” This "Diagram of the causes of mortality in the army in the East" was published in Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency, and Hospital Administration of the British Army and sent to Queen Victoria in 1858.

This experience influenced her later career and she campaigned for sanitary living conditions, knowing how dangerous unsanitary conditions can be to survival. She also made extensive use of similar polar area diagrams on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War, or sanitation conditions of the British army in rural India, to make such statistics transparent to Members of Parliament and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports.

In 1859, Nightingale was elected the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society. She later became an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

Though her own opinion of other women was often harsh, she has been credited with contributing to feminist literature with a book she wrote while sorting out her thoughts on her role in the world, including the essay Cassandra, which protested the over-feminisation of women into near helplessness. She helped abolish laws regulating prostitution that were overly harsh to women. She also clearly expanded the acceptable forms of female participation in the workforce.

This, and in particularly, the way she insisted on making decisions based on scientific evidence, and using data to save lives, makes her an apt addition to the women in science portrait series.

*My grandfather was a very strong man, who fainted when diagnosed with a fully treatable skin cancer, despite enduring rhematoid arthritis without complaint. My father famously fainted during his pre-natal class. My brother fainted during a presentation on why junior high school students shouldn't smoke, which included an image of a damaged lung. My other brother famously fainted during Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, twice. I fainted during a tour of McMaster Medical School, while they explained what happened to corpses at the morgue. They sat me down, got me water and told me not to be discouraged from a career in medicine, while I looked at them in disbelief and insisted I never wanted one.

Reflection, Moon and Ocean Linocut & a Tattoo

Last fall, Tina Gleason contacted to ask my permission to get a version of my 'Reflection' linocut tattooed on her arm. She lamented that the linocut itself is no longer available. It's unusual for me, but Reflection was a reduction linocut. That means that I first carved the block to produce the 'background' silver layer and printed it on lovely dark blue Japanese washi with silk fibres. Then I carved further to produce the upper white layer. That means that 'Reflection' is limited edition. I cannot print more since the block for the silver layer exists no more. You may recall that another of my prints once inspired a tattoo, which I take as a great compliment. I was glad to hear she wanted my blessing and very flattered that she felt so strongly that she wanted the image permanently tattooed on her body - her first tattoo! She wrote today to say she finally found the right tattoo artist and had the image tattooed on her forearm by Deirdre Doyle in Cambridge, MA. Above you can see the original linocut, the sketch on her arm and the final tattoo. I love how this sort of transmission of artistic ideas, where the translation to another medium means that something altogether new is created. To me this sort of reinvention, especially for something non-commercial, and in fact personal and intimate, is using the image as inspiration to create a derivative work which I can and do welcome!

Monday, March 10, 2014

Cosmos on the Etsy Blog

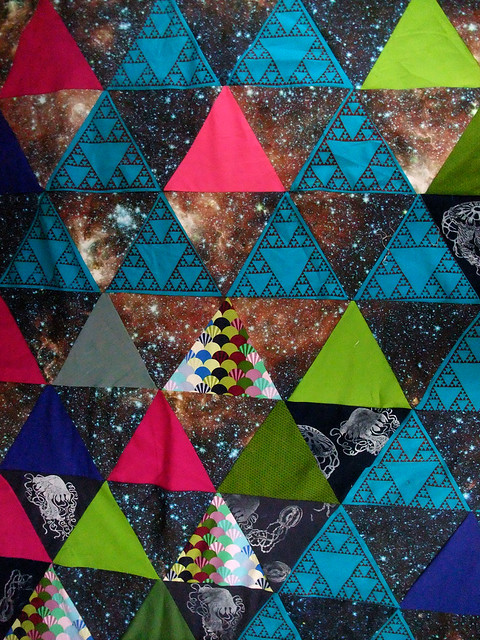

I was reading the Etsy blog this morning and enjoying their collection inspired by the reboot of Carl Sagan's Cosmos: A Personal Voyage - Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey hosted by Neil Degrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History. I was busily adding items to my favorites lists (not just my collection of science-themed items, but my collection of things I want myself, for the befuddled gift-buyers in my life), when I scrolled down and saw my own portrait of Jocelyn Bell Burnell! I'm flattered to be in this company. And yes, you should buy me the Mars globe and the screenprinted moon pillowcases with glow-in-the-dark constellations cause they would go perfectly with my own quilt with NASA imagery and glow-in-the-dark stitching. I mean really.

Friday, March 7, 2014

Women Scientist Portraits on Scientific American.com

|

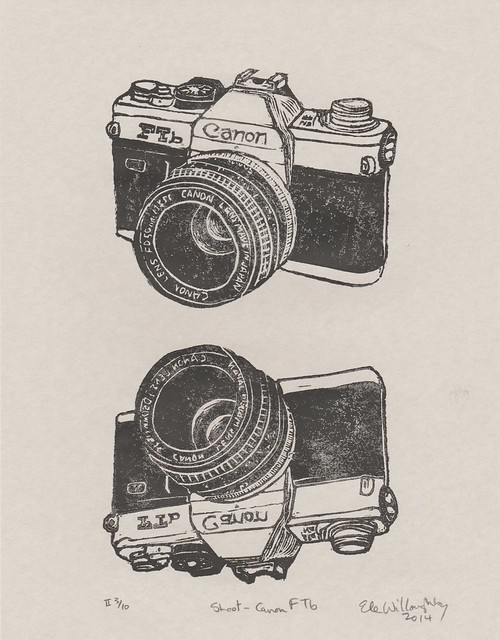

| Inge Lehmann and the Earth's Inner Core linocut on Japanese kozo paper, 2011, 20.5 cm x 20.5 cm |

Just in time for International Women's Day, Scientific American has published Maia Weinstock's photo essay about female scientists portrayed in art: 15 Works of Art Depicting Women in Science; Visualizing notable women in the STEM fields through the lens of fine art. There are some really wonderful portraits of great scientists. She writes about each artist and their inspiration. I'm flattered to be included, along with my portrait of the great Danish pioneer of whole Earth seismology, Inge Lehmann. Lehmann is an apt selection; not only did she make the revolutionary discovery of the Earth's inner core (and find the evidence in what others had mistaken for noise), but she wasn't shy about frankly discussing how women's contributions to science were all too often overlooked.

I love also how she points out that the idea that science and art are divorced is only recent, and the contemporary move to go from STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) back to STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math). If you read carefully, you'll also glean the inspiration for my most recent portraits of female scientists: Maia will be curating a women-in-STEM art exhibit at the Art.Science.Gallery. in Austin, Texas, from September 13 through October 15, 2014, which will include some of the works and artists from her article, like me!

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

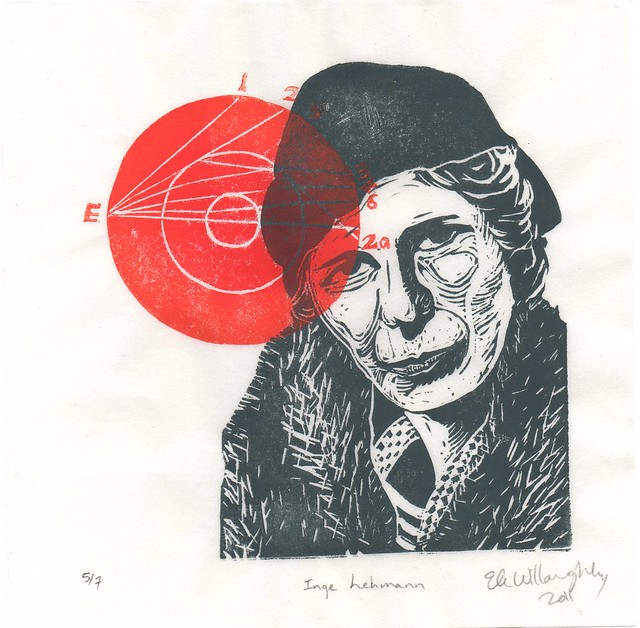

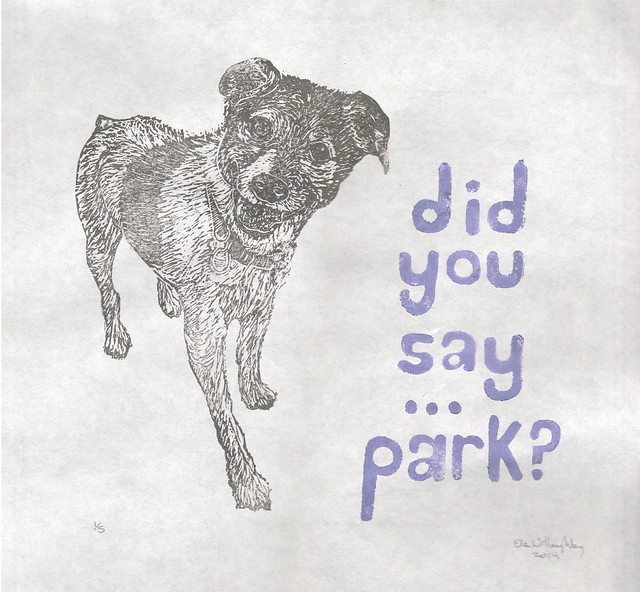

Did you say park?

I made a custom order pillow for the husband of a lovely customer, of their delightful looking dog. He really did appear to have the sweetest nature in all the photos. So, I wanted to use the block with the dog's portrait, and I could only imagine I'd captured that moment the dog heard the word, "park".

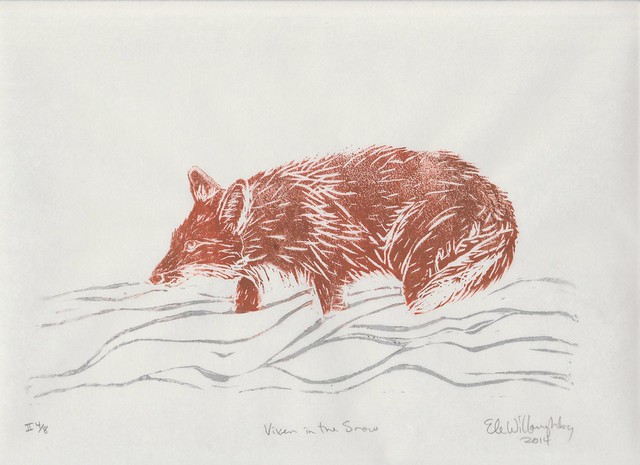

Lately, I've been printing second editions of popular prints, if I've run out of stock. Like my Vixen in the Snow, Aurora Borealis with the polar bear, and screech owl. Next, I plan some quail and maybe portraits of Minouette, herself.